Combating Kidney Disease by Studying Zebrafish

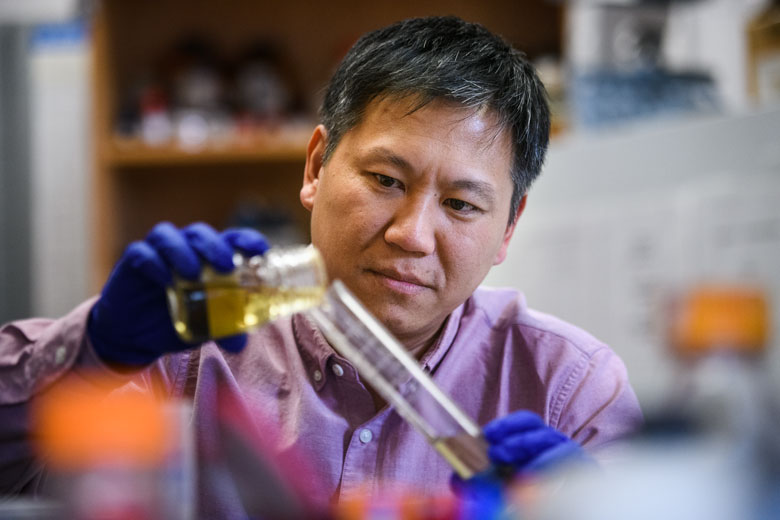

The National Kidney Foundation reports the two main causes of kidney disease are diabetes and high blood pressure. In 2018, the American Diabetes Association reported that 10.5 percent of the US population—34.2 million people—suffer from diabetes. The Centers for Disease Control reported in 2017 that 108 million adults in the United States—nearly half—suffer from high blood pressure. Cuong Diep's research on the zebrafish's ability to regenerate kidneys has been published in several journal articles. Diep took a few minutes to talk about how his work might solve a growing worldwide problem for humans and how he puts students in the IUP Department of Biology on the case.

What sparked your interest in kidney regeneration?

Kidney disease is a problem worldwide, and it's going to get worse over time. The options for treating kidney disease are limited, and new research is needed to broaden the options. We experiment with zebrafish because they can regenerate their kidneys—something that humans cannot do. They do so by using a specialized stem cell. Humans don't have these cells, but fish do. If we can understand how they do this and where these cells come from, then we might be able to translate that to humans.

More about Cuong Diep

- PhD, Penn State University, University College of Medicine, 2006

- Harvard Medical School/Massachusetts General Hospital (Postdoctoral Fellow), 2006-2010

- University of Pittsburgh (Visiting Research Associate), 2010-2011

Exciting Update Since Diep's Interview

One of his students was selected by the National Science Foundation to participate in the highly competitive Research Experience for Undergraduates program.

Courses Diep Teaches

- BIOL 203 Principles of Genetics and Development

- BIOL 241 Introduction to Medical Microbiology

- BIOL 300 Genetics in Medicine and Nutrition

- BIOC 481 Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine

What do you hope your research will achieve?

We want to understand how the kidney forms and how it regenerates. The approaches we take include understanding what genes are involved, how those genes regulate the stem cells, how those stem cells turn into new kidney tissue, and the molecular mechanism of how things work. We're also interested in looking at small molecules, similar to drugs. We want to find new molecules and understand how they affect kidney development. Do they make it better? Do they make it worse? If you can find those types of molecules, you can use them to understand how the kidney forms and what those molecules are affecting. The reason we study both development and regeneration is that both processes are very similar. The way you make something is very similar to how you remake it during regeneration. If you can understand one process, then it can help you understand the other process, and vice versa.

What's the most important thing students learn in your lab?

I push them to be independent. Once I've trained them on how to do something, they work in the lab by themselves. If they have questions, they can contact me. From that, they learn independence, and they learn to be confident. They can achieve things without me, and I'm just there to guide them. Many students who've worked in my lab start out as freshmen and sophomores. My current student joined my lab as a first-semester freshman, and she's been independent in the lab for the last year.

What do you like best about your job?

One of the things I enjoy that rises above teaching is discussing this kind of research and discovery with students. Many of them keep track of the latest [scientific] events, and we discuss them like colleagues. That's really enjoyable.