IUP speech-language pathology faculty members had a problem. How could they provide necessary clinical hours for their students in a simulation laboratory they didn't have? Add to the problem that a typical lab costs close to $150,000 to create. Their solution was rooted in collaboration, innovation, and a lot of hard work.

Every year in the United States almost 800,000 people suffer a stroke. Furthermore, respiratory intubation and mechanical ventilation is the third most common procedure performed in hospitals, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Those medical events can damage functions of the throat that are essential to the ability to speak and to swallow. In acute-care settings, as patients begin to recover, frequently they are evaluated by a speech-language pathologist. Various tests are performed on the patient to determine how to improve coordination of breathing and swallowing to prevent choking dehydration or aspiration pneumonia.

Faculty members in IUP's Speech-Language Pathology program had a vision. The beneficiaries would be their students. The outcome would check all the boxes: Students with more confidence. The medical industry filling a gap. Acute-care patients potentially with better outcomes. To prepare students to graduate and move into one of the top 10 fastest-growing occupations in the US, the challenge was clear: construct a simulation laboratory and corresponding curriculum to meet the need, and do it on a shoestring budget.

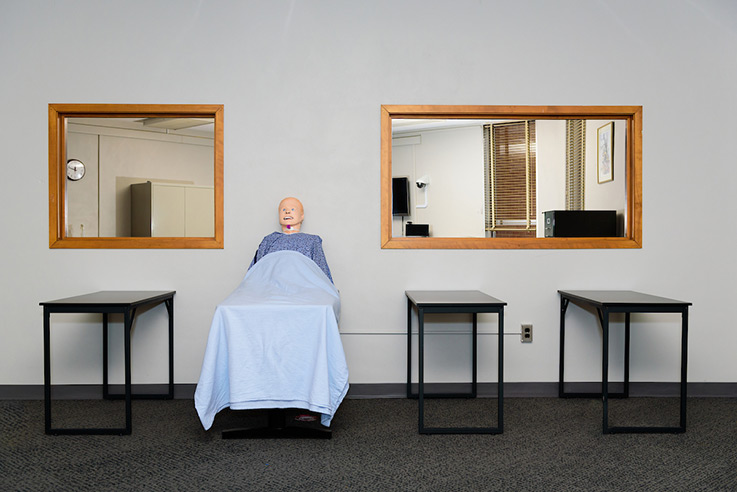

Utilizing available space inside Davis Hall, speech-language pathology faculty members Lori Lombard and Erin Clark transformed 150 square feet of space, previously a computer lab, into an innovative, acute-care simulation laboratory for use solely by speech-language pathology students. While designing the lab, faculty members made an effort to incorporate some basic features that provide a more realistic experience for students: a curtain to be pulled for privacy, a sink for handwashing, and a gloving station.

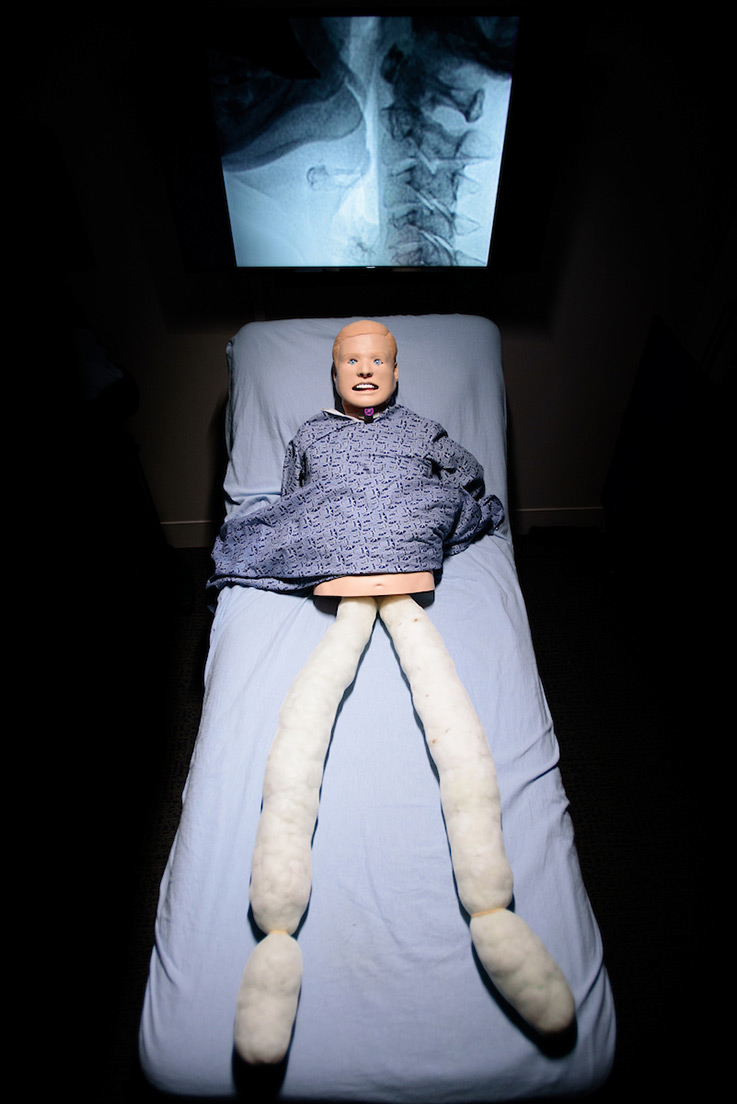

Kevin, as he's affectionately called by students, is a half-manikin, because speech and language students are focused on the head and neck area. Purchasing a half-torso, static manikin and stuffing pantyhose with cotton balls to simulate legs under the bedsheet saved the program $78,000.

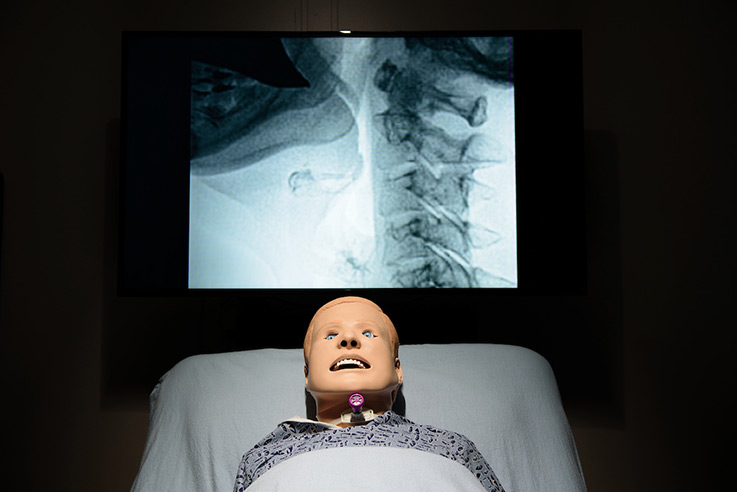

The computer monitor behind Kevin allows students to watch video clips of fluoroscopic or endoscopic swallowing evaluations for real-time clinical decision making. The technology turns what would be a typical hospital bedroom into a radiology suite for a more realistic bedside experience. In the foreground, a smaller computer monitor duplicates what students are viewing in the room and is where a faculty member would manipulate learning content.

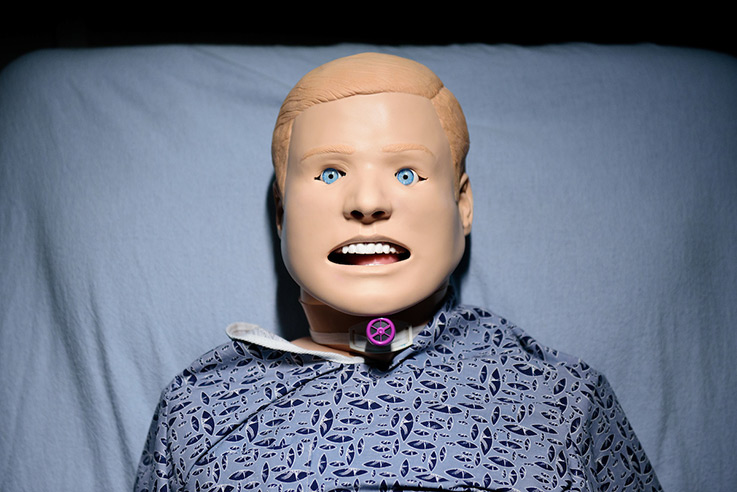

Kevin, a light-skinned, male static manikin, is wearing a hospital gown and is outfitted with a tracheostomy, dentures, a stomach, and lungs. He can experience aspiration during a “swallow.” Lombard and Clark noted in their research that the low-cost, half-torso manikin is offered only in light skin. Other options for skin color and facial features are available with more expensive, full-sized manikins and should be considered to offer a diverse learning experience for students.

The current one-bed simulation laboratory was established in 2018 and housed its first acute-care simulation course for IUP graduate students in speech-language pathology in 2019. While the current lab provides necessary clinical contact hours required for certification, only the student participating in the hands-on lesson can count the hours. Lombard and Clark are looking to expand the lab to a four-bed facility, allowing more students to get necessary training hours during a clinical simulation. The estimated cost to purchase beds, manikins, computers, and monitors with control stations and to outfit the classroom is estimated at $35,000.