In the third and final installment of the Constitution in Crisis series, Department of Political Science faculty members David Chambers and Gwen Torges explain what sedition is and how it relates to the events in Washington, DC, on January 6.

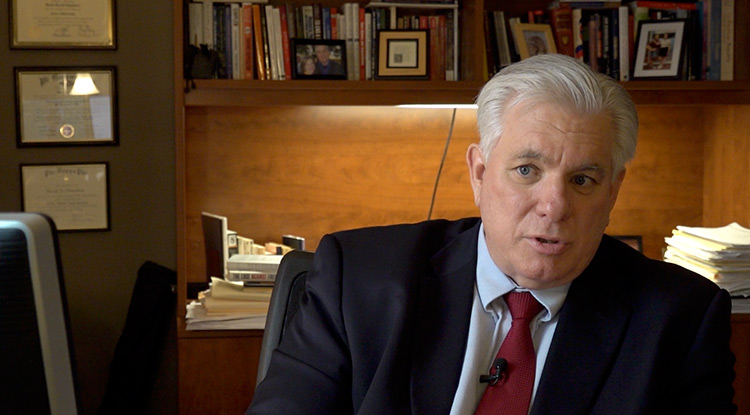

David Chambers

- Bachelor's Degree, Political Science, Idaho State University

- Master's Degree, Public Administration, Idaho State University

- Doctoral Degree, American Public Policy, University of Illinois at Urbana

Courses Taught

- PLSC 300/500 Research Methods

- PLSC 350/550 The Presidency

- PLSC 355/555 Intergovernmental Relations

- PLSC 666 Public Policy Analysis

- PLSC 671 Seminar in Public Administration

Gwen Torges

- Bachelor's Degree, Communications, California State-Fullerton

- Master's Degree, Political Science, University of Arizona

- Doctoral Degree, Political Science, University of Arizona

Classes Taught

- PLSC 111 American Politics

- PLSC 250 Public Policy

- PLSC 358/558 Judicial Process

- PLSC 359/559 Constitutional Law and Civil Liberties

- PLSC 405 Sexuality and the Law

We keep hearing about “seditious conspiracy” and “treason.” What's the difference between the two?

Torges: The difference between seditious conspiracy and treason is that treason is the actual act of working to seriously harm the government, whereas seditious conspiracy is a step before that, where you're planning violence against the government.

Chambers: You could argue that if Trump were charged with seditious conspiracy, it's because he hoped his words would lead to something, to some action.

Congress passed an act against sedition, didn't it?

Torges: The Sedition Act that was passed in 1918 applied only during times of war, and it was repealed in 1920. The 1918 law was very broad and criminalized saying or writing negative things about the government that would put the government in a negative light. However, “seditious conspiracy” is still a federal felony, but it requires much more than simply making the government look bad. The current law forbids inciting violence that delays execution of a law.

President Trump's words are protected by free speech, correct? How could he be charged with a crime just for speaking to the crowd?

Torges: Up until January 6, I would have said that any case against someone for seditious conspiracy would have been laughed out of court, because it would have been protected by the First Amendment. Now it's easier to imagine. But if President Trump were prosecuted in a regular federal court for inciting the violence at the Capitol, the courts would use the two-part test set out in the Brandenburg v. Ohio case. Trump's speech would be protected unless his words created a strong likelihood of imminent illegal action and his words were the direct cause of the action. I can conceive of a lawyer putting together such an argument, but I don't think it would satisfy the courts.

Chambers: I think that's why the article of impeachment uses the phrase “willful incitement to violence.” It's a lesser standard that can more easily be connected to an action.

What's the Brandenburg case about?

Torges: The case, from 1969, involved a Ku Klux Klan leader who, at a rally, accused the government of trying to suppress the rights of Whites. He announced there would be a Klan march on July Fourth in DC and that the group might seek “revengence” on government officials. The Klan leader was charged and convicted of violating an Ohio law that made it illegal to advocate violence. His lawyers appealed, saying the law violated the First Amendment, and the Supreme Court agreed. It said that just advocating violence was protected by the Constitution. The Klan leader said he was talking about violence in the future. Speech can be punished only when the comments directly support imminent violence.

Would these potential charges affect the ongoing impeachment process?

Chambers: Seditious conspiracy doesn't play into the impeachment process, because the impeachment process doesn't rise to the same standard. Because an impeachment is a political process, there is no denial of life, liberty, or property. The only thing at stake is whether the president gets to remain in the position.

What about Rudy Giuliani? He said he wanted to have a “trial by combat.” He's not an elected official, so he has First Amendment protection, doesn't he?

Torges: You don't have to hold an office to be charged with seditious conspiracy. Again, an argument could be made that his comments were part of what led to the violence, but I don't think it would pass the Brandenburg test, which means he'd be protected by the First Amendment.

Note: This is the third and final story in the series Constitution in Crisis, about constitutional topics currently in the news.