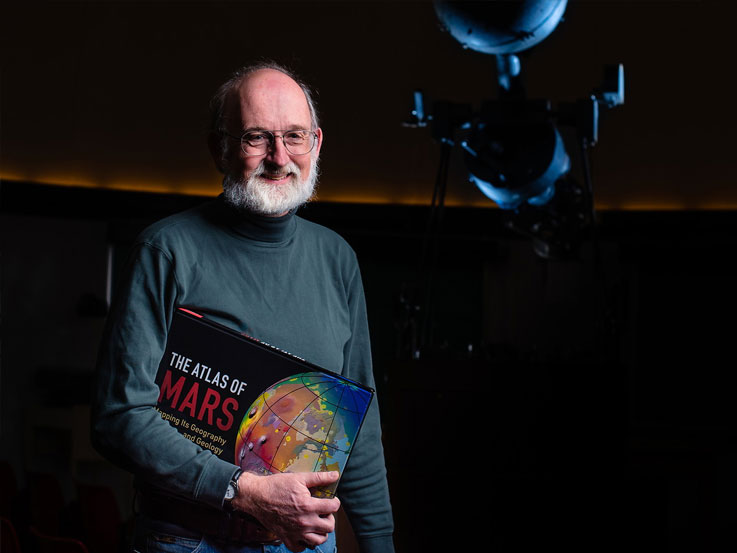

Ken Coles hasn't been to Mars, but he knows a lot about the Red Planet. Actually, he's written the book on it.

More about Ken Coles

- PhD, Geology, Columbia University

- MPhil, Columbia University

- MS, Geology, California Institute of Technology

- BS, Geology, California Institute of Technology

Courses Coles Teaches

- GEOS 105/106 Exploring the Universe and Lab

- GEOS 154 Exploration of Space

- GEOS 403/404 Newfoundland Seminar and Field Workshop

- GEOS 323 Geophysics

- GEOS 341 Planetary Geology

- GEOS 342 Stellar Astronomy

Coles, a faculty member in the Department of Geoscience, specializes in astronomy, space exploration, and anything scientific that deals with non-earthly bodies. In 2019, he, along with Ken Tanaka of the US Geological Survey and Phil Christensen of Arizona State University, wrote The Atlas of Mars: Mapping Its Geography and Geology, which gives a better understanding of Earth's next-door neighbor.

So, it's no surprise Coles has been eagerly following NASA's Perseverance rover, which landed on Mars in February and has been sending back photos and other information. Coles recently discussed Perseverance's objectives, why they're relevant to us Earthlings—and if the rover is likely to encounter little green aliens.

Where on Mars has Perseverance landed?

Mars is divided into two big halves. The northern half has low elevation and is smooth. The southern half is higher in elevation, rugged, and hammered up with craters and mountains and things like that. Most of the missions that have landed on Mars have landed near the equator, where it makes sense to land, … and [Perseverance] is there, too.

It landed in the Jezero Crater. The crater is about 40 kilometers across. It contains a feature that looks like a bird-foot delta that you'd see on a map of Louisiana if the water had been drained out.

What are they looking for?

Measurements made from Mars's orbit suggest that the Jezero Crater has mineral structures that have water or sulfates in them, suggesting they were wet at one point.

But Mars has a history of making us think twice, because most of what we know we first learned from orbit. A prime example would be the Spirit rover, which went into the Gusev Crater in 2004. The Gusev Crater has a notch on the northern end, which opens to the low, northern plains, and the southern end, with a big, winding channel coming into it. It certainly looks like water had been there, like it was a lake that drained out. Well, Spirit went in, and what it found was that the bottom of the crater was volcanic rock. That means in the several billions of years after the lake might have existed, there had been a volcanic eruption there that covered any lake deposits.

So, it'll be interesting to see what they do with Perseverance. They'll be very cautious in drawing conclusions until they have some direct measurements.

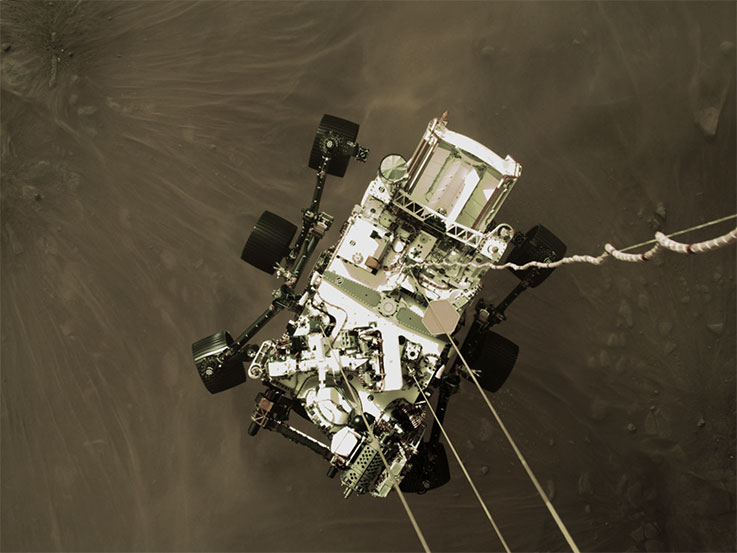

NASA's Perseverance rover as it touched down on Mars on February 18.

NASA's Perseverance rover takes its first drive on Mars on March 4.

Why is this mission important?

One of the reasons is to talk about the early history of the solar system.

For example, where did Earth get its water? Did the Earth start out with water, or did it come later? One thing about Earth is that it's like a chalk board that has been erased a whole bunch of times. We're on an active planet that has earthquakes and volcanoes and water cycles and you name it, so the great majority of rocks on our planet are relatively young.

If you go to a place like Mars, you see a lot of fairly old rocks. And because of the atmosphere, you can presumably see what Earth may have looked like, and Mars as well, early in the history of the solar system.

Some people say it's just pure research in planetary science. And then, of course, there are a few people who want to know if we can find life on Mars.

Well …?

My stock answer is this: mathematicians say that, statistically, it is likely that life has started several times, because the galaxy is such an enormous place. For us to find it in the first place we look would be amazingly good luck. I'm not betting on it right off the bat. But who knows? We've been wrong before.

Are they also trying to determine if humans could someday live on Mars?

Students ask me that a lot. They say, “What is the most difficult thing about traveling to Mars?” My answer is the fragility of the human organism. We're well-adapted to live on Earth, but we're not necessarily well-adapted to live on the surface of other places. We'd have to figure out how to protect ourselves from all the various hazards.

How much of Mars do we know about?

It's hard to say, because in 100 years, they'll say we didn't know anything about Mars. But it's like looking at Earth and saying, “This much is mountains, and this much is water, and this much is grasslands.” You can find that out from orbit. But to say that “this part of the Mississippi River did this” or “this glacier flowed over here” are things you have to discover on the surface.

I don't think any scientist is going to pat themselves on the back and say it's all done. Science isn't a bunch of answers you memorize; it's a way of asking questions.

As much as you know about Mars, are you still fascinated by what you're learning?

Oh, yeah, for sure. I never got tired of working on the book, even though it took six years. I never get tired of looking at those pictures and trying to understand what they show. I still get excited about everything I teach. I mean, my job at IUP—teaching astronomy—is like getting paid to eat ice cream. I love it.