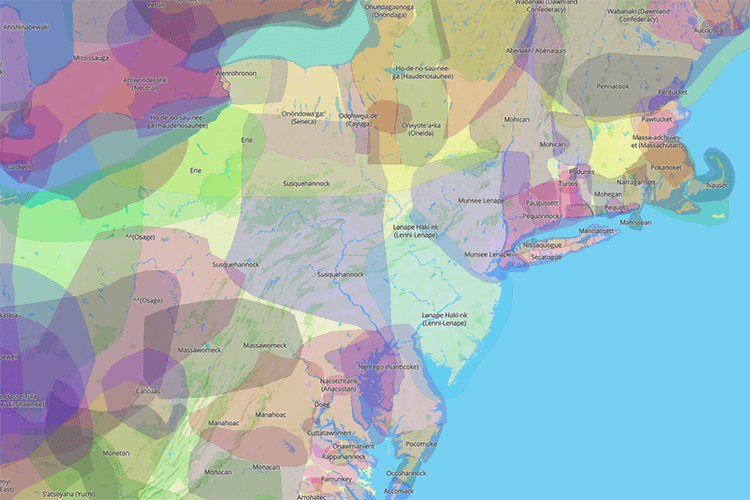

A new movement to “decolonize” Thanksgiving keeps the positive traditions while turning away from hurtful stereotypes of Native Americans. Thanksgiving dinner, family, gratitude, community, and generosity are emphasized while acknowledging Native American history and the contributions indigenous people have made to developing today’s foods.

A new movement to “decolonize” Thanksgiving keeps the positive traditions while turning away from hurtful stereotypes of Native Americans. Thanksgiving dinner, family, gratitude, community, and generosity are emphasized while acknowledging Native American history and the contributions indigenous people have made to developing today’s foods.

Learn More History at “Decolonizing Your Thanksgiving”

Want to hear more? The Center for Multicultural Student Leadership and Engagement and the Native American Awareness Council will present a Lunch and Learn event titled “Decolonizing Your Thanksgiving Meal.”

The event, which features a presentation by Abbie Adams, associate professor of anthropology and chair of the Native American Awareness Council, will be held Wednesday, November 17, from 11:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. (during the Crimson Common Hour) in the Great Room in Elkin Hall.

Thanksgiving dinner can be a wonderful chance to spend time with family while sharing a special meal. It’s the main way we celebrate the holiday, and it’s a positive and valued tradition that many enjoy.

While Thanksgiving dinner can be linked back to the holiday’s true history as a harvest feast, many of the stories told about the first Thanksgiving do not measure up against the indigenous perspective. Instead, they promote hurtful stereotypes.

There is a movement to enjoy what is positive about the holiday while turning away from one-dimensional misrepresentations of Native Americans. This newer approach is informed by indigenous world views—such as balance instead of excess.

It keeps the focus on Thanksgiving dinner and being together with family while exploring the authentic history of those times and the tremendous contributions Native Americans have made in developing the foods we eat today.

“It is important to set the record straight, acknowledge Native Peoples, debunk myths, and show Native Americans as contemporary people with dynamic, thriving cultures who have profoundly impacted our current food system,” said Abbie Adams, a faculty member in the Department of Anthropology. Adams has researched this topic and has done presentations to help people understand the holiday’s history and what is meant by “decolonizing” Thanksgiving.

“It means going beyond the harmful ‘pilgrims and Indians’ narrative and focusing on common values: generosity, gratitude, community, and good food,” she said.

“It is important to set the record straight, acknowledge Native Peoples, debunk myths, and show Native Americans as contemporary people with dynamic, thriving cultures who have profoundly impacted our current food system.”

Not All Settlers Were Pilgrims

The true history of Thanksgiving is far more complex than what you may remember hearing while you were tracing your hand to make a turkey in elementary school.

For example, the “pilgrims” weren’t actually all pilgrims. Also, a famous Native American who played a key role in Thanksgiving stories knew English only because he had been captured as a slave years before. And, the first Thanksgiving might not have included any turkey.

The colonists who took part in the first Thanksgiving at what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts, were settlers—not pilgrims fleeing religious persecution, Adams explained.

“The pilgrims (who did not call themselves pilgrims) did not come to the US seeking religious freedom; they already had that in Holland,” she said. “They came here as part of a commercial venture.”

Squanto’s Story

Squanto, whose full name was Tisquantum, is known from elementary-school history as a “friendly Indian who helped the settlers learn to plant corn.” He did help the new arrivals and could speak English, but there is more to his story.

Years before that first Thanksgiving, Tisquantum and others in his village were tricked into boarding a boat with the promise of trading goods. He and about 19 other people were captured as slaves and taken to Spain. His sale as a slave was blocked by friars, and he learned to speak English while in Europe.

About five years later, he was able to return to North America because of his value as an intermediary and interpreter. He returned home to his village only to find that everyone there had died from disease. He was the sole survivor of his village and family.

First Dinner Wasn’t a Planned Gathering, and Foods Varied

It’s true that the native Wampanoag people who lived near what is now Plymouth formed some kind of connection with the early settlers, though history points to it as more of an agreement to help each other if attacked by their mutual enemies.

It also is thought to have been a way for the Wampanoags to navigate the difficult, complex situation they faced with a neighboring enemy tribe as well as with settlers, traders, and even slave traders arriving on the coast.

The shared dinner might not have been planned, but rather developed from circumstances. The settlers had just had a good harvest and a very successful hunting expedition that included many wild birds, according to information Adams shares in her presentation.

A letter written by Edward Winslow, an English leader who attended the first Thanksgiving, mentions the firing of guns after the hunt.

He wrote:

“At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest, their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain and others.”

The Wampanoag hold a harvest feast, called Nikkomosachmiawene, or Grand Sachem’s [Say-Chem’s] Council Feast. Adams explained it was because of this feast that the Wampanoag had amassed the food to help the settlers.

According to many historical accounts, there is little evidence of turkey being eaten at that 1621 meal, but there was wild fowl (most likely pigeon, goose, or duck). Sweet potatoes were not yet grown in North America, and cranberries were not a likely dessert food, because sugar was unaffordable. Other items on the table included venison, pumpkin, beans, and corn.

The First Thanksgiving and a Day of Mourning

What Really Happened at the First Thanksgiving? The Wampanoag Side of the Tale

The Mashpee Wampanoag tribal historian talks about Thanksgiving.

Ironically, the first official “Day of Thanksgiving” was proclaimed 16 years later, in 1637, by Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop, Adams said. He did so to celebrate the safe return of English colonists from Mystic, Connecticut, after they had massacred 600 Pequot [Pee-qwat] People.

Throughout the early 1800s, magazine editor Sarah Hale lobbied hard for a national day of thanksgiving, petitioning 13 presidents. In 1863, during the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln made Thanksgiving Day a national holiday, hoping that it would help unite the country.

Native Americans living in Plymouth commemorate a different holiday on Thanksgiving Day—a National Day of Mourning. Adams explained that it was started by Wamsutta James, a Native American man who was asked to speak at a community Thanksgiving Day event in the Plymouth area in 1970. When event organizers saw what he had written and was going to say about how Native American people had been treated, they did not let him speak.

That year, he and hundreds of other Native Americans and supporters established Mourning Rock in Plymouth and the Day of Mourning, commemorated on Thanksgiving Day to give a voice to the hardships Native Americans have suffered.

James’s son still leads the Day of Mourning with members of the United American Indians of New England, a group James formed.

Add a New Dish from the Many Foods Native People Brought to the World Table

November is National Native American Awareness Month, so it’s the perfect time to celebrate the powerful role indigenous people have played in developing the foods we enjoy year-round.

“Did you know that indigenous America gave the world three-fifths of the crops now in cultivation?” said Adams, who encourages people to include a food originally grown in the area in their Thanksgiving meal. It can be a way to honor the contributions Native Americans have made in the science of food cultivation, developing many of the varieties we eat today.

Some of these foods might already be part of your Thanksgiving dinner:

- Beans

- Squash

- Corn (Maize)

- Pumpkins

- Potatoes

- Chocolate

- Vanilla

- Tomatoes

Innovative Farming Techniques

In addition to developing different varieties of foods, Native Americans initiated farming techniques that improved their crops and that are backed by agricultural science.

For example, in one story about Squanto, he is said to have instructed settlers to plant fish heads—which we now know would serve as excellent fertilizer—with their seeds.

Another example is the “three sisters,” an innovative approach that Native Americans used for planting beans, corn, and squash. By planting seeds for all three together, the corn creates a stalk for the beans to climb, while the squash’s leaves shade the ground and keep moisture in. The beans also help the soil.

As you pass the corn, beans, and potatoes around the table this Thanksgiving, your family is sharing the legacy of Native American farming.