Looking west between Leonard Hall and Stapleton Library on the first day of fall 2023 classes

IUP Aims Not Just to Survive Enrollment Drop but to Grow Stronger

It wasn’t all that long ago that IUP seemed to be the perfect size. It wasn’t as large as the big-name schools in the region, but it felt more personal. And it had more academic offerings than many of the small private colleges in the region, making it the destination for more than 10,000 students every year, most of whom came from western Pennsylvania.

IUP was the largest school in Pennsylvania’s State System of Higher Education, its only PhD-granting institution, and the envy of many of its sister schools.

But for many reasons––some beyond the university’s control––enrollment has declined dramatically over the past decade. This has caused a cascade of problems, leaving IUP to face one of its most difficult times, with finances, workforce, programs, and facilities all adversely affected.

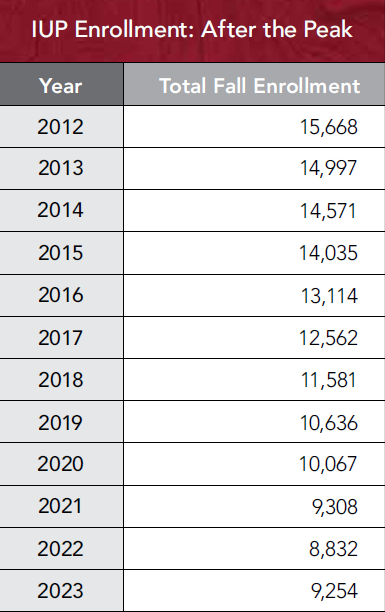

“We rely on our enrollment,” said Debra Fitzsimons, IUP’s vice president for Administration and Finance. “It drives the decisions we make, from the number of faculty and staff to the number of course offerings to the number of buildings we have. It affects everything. We’ve dropped over 40 percent in enrollment, and that’s huge.”

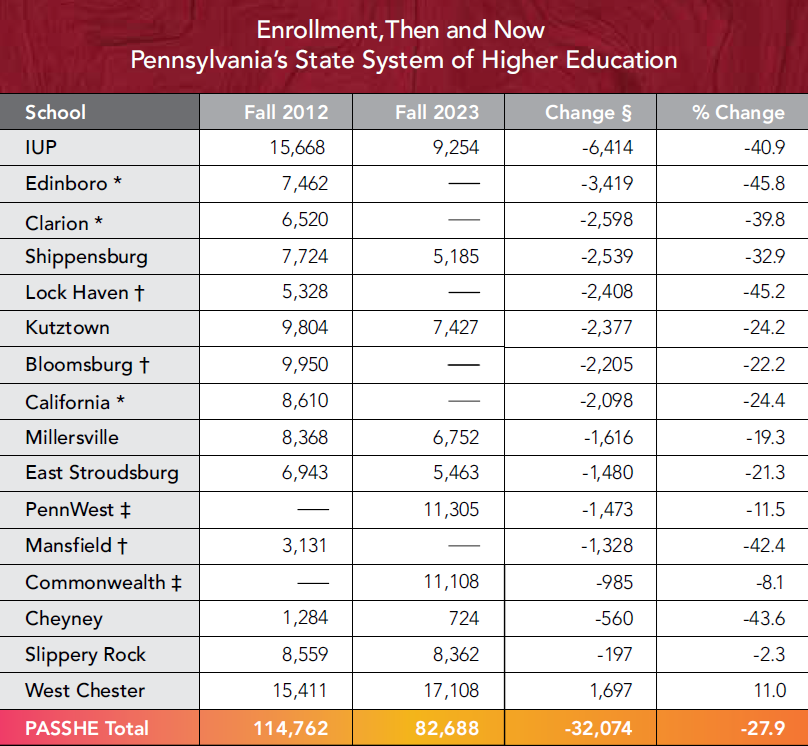

IUP is not alone in this regard. The State System, collectively, has lost more than 32,000 students, or 27.9 percent, since 2012-13. Every school except West Chester in the State System has fewer students today than it did then.

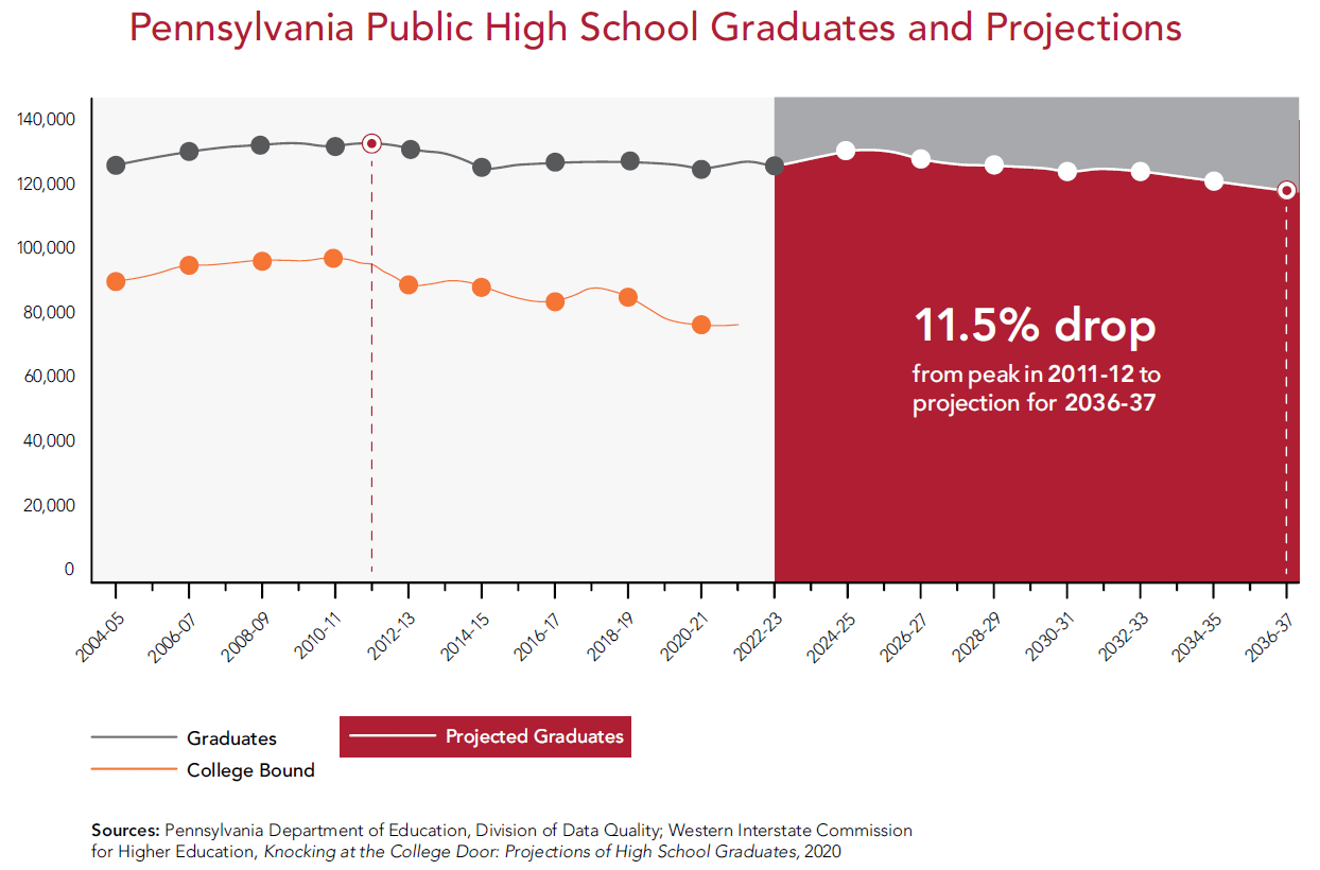

It’s not just the State System that’s hurting in Pennsylvania. The state’s two biggest-name schools, Pitt and Penn State, are holding steady or growing slightly overall, but their branch campuses are experiencing sharp declines. From 2010 to 2022, enrollment at Pitt’s four branch campuses declined an average of 36 percent, while enrollment at 18 of Penn State’s 19 satellite sites dropped an average of 30 percent. College enrollment across the country is also sagging. Nationally, the number of 18- to 24-year-olds enrolled in college is down approximately 1.2 million from its peak in 2011.

In its little corner of the higher ed world, IUP is taking on the challenge of not just weathering the storm, but becoming better and stronger, which requires scrutinizing some of its old ways.

“We’re going to have a different population set for the next 50 years than we’ve had in the past 50 years,” IUP President Michael Driscoll said. “We have to change how we think about enrollment. But we are rich in smart people who are dedicated to the mission and the institution. We have an incredible alumni base and an incredible reputation that we have earned. But we must be willing to change almost all our assumptions about how we should operate if we are to remain viable and strong going forward.”

The Harsh Truth

By drawing mostly from its fertile western Pennsylvania backyard, IUP averaged just over 13,000 students per year for most of the past six decades. The university reached its high-water mark for enrollment in 2012-13, but beginning the following school year, its head count began decreasing. In 2021-22, it fell below 10,000 for the first time since 1968-69.

Since 2012-13, IUP’s enrollment has dropped by more than 6,000 students.

“I think it’s appropriate to talk about this as being a disruptive time in higher education,” Driscoll said.

So how did it come to this, and what can be done about it? The answers are as complex as the problem.

Driscoll’s first day as IUP’s president was July 1, 2012, and about two months later the university announced its highest enrollment ever: 15,379 (not counting students in clock-hour programs, such as Culinary Arts and Criminal Justice Training). Times were good, especially because head counts at several other State System schools were either stagnant or declining, and IUP continued to have the most students among the 14 universities.

But a little more than a decade ago, the population decline in western Pennsylvania began to accelerate, and IUP’s head count started to slide.

“We had been coming off a period since the mid-1970s when the talk about enrollment was almost always about growth,” Driscoll said. “We were set apart from the rest of the system in that they were declining while we were still growing. The demographic information was out there, but there was not this recognition that we were really headed downward. I don’t think, in the early stages, that anybody was talking about it or making decisions based on it.”

According to the Pennsylvania Department of Education, from 2013-14 to 2022-23, the total number of students from prekindergarten through grade 12 in western Pennsylvania public schools dropped by about 42,000, or nearly 9 percent. Indiana County, IUP’s home turf, has suffered heavily: last year, there were 1,037 fewer students enrolled in the county’s schools than there were 10 years ago, a drop of 11.2 percent.

“Demographics are a huge problem,” said Stacy Hopkins ’94, M’96, who has served as IUP’s executive director of Undergraduate Admissions since 2015.

Yet demographics are not the whole problem. Other factors have contributed to the enrollment decline.

Competition and Perception

To use a fishing analogy, there are not just fewer fish in the pond today; there are more baited hooks. In Pennsylvania, high school graduates have nearly 300 options for colleges, universities, and trade schools. Only three states––California, Texas, and New York––have more. With some of the surrounding states also suffering from population declines, many of their colleges and universities have crossed the border at increasing frequency and dropped lines in Pennsylvania’s pond.

At the college fair sponsored by the National Association for College Admission Counseling in Pittsburgh in February, there were 30 schools from New York and 28 from Ohio. Also, the US Army staffed a booth, and several technical colleges were there, hoping to lure Pennsylvania students.

Source: IUP Office of Institutional Research, Planning, and Assessment

“Students have many more options than they used to,” Hopkins said. “At the college fairs, there used to be primarily four-year colleges. Now, they’ve got two-year nursing schools, community colleges, the military, realtors, and the trades. It’s very different than it used to be.”

There are also more four-year, in-state college options for western Pennsylvania students. Within the past 40 years, at least three colleges in the region became coeducational, while a few more were created or expanded with branch campuses.

But the problem goes further than demographics and competition. In recent years, there has been a national discussion about the perceived value of a college education. Some students are forgoing the traditional route and heading into entry-level jobs after high school. Some are taking a “gap year” before starting college, and many are going into trades to make good money right away. Not surprisingly, a 2021 report showed that one in three high school graduates who did not go to college believed higher education was “a waste of money.”

“At college fairs,” Hopkins said, “we meet students who have just walked away from a table where someone tells them they can start as an electrical lineman first-year apprentice making up to $35 an hour. Now they’re thinking, ‘Why would I go in debt for college when I could work and make money with no debt and have the potential to make six figures once the apprentice program is complete?’ That’s tough for any college to compete with.”

The discussion about the value of higher education is based in part on cost. For schools like IUP––schools at which taxpayer support is key to keeping tuition low––the continued lack of appropriate funding by the commonwealth has made it harder to afford college, so many students are avoiding that burden.

And while Pennsylvania funds IUP and the State System with hundreds of millions of dollars every year, the state still ranks near the bottom in higher ed spending. In 2022, it ranked 49th out of 50 states in funding for public higher education per full-time student.

Although the State System determines the price of tuition for its schools, each varies in the cost for fees, housing, and dining. In 2016, hoping to give students more flexibility in scheduling, IUP enacted a per-credit tuition plan, replacing a flat rate. Combined with an increase in student fees designed to bring in more revenue as enrollment dropped, the plan wasn’t as affordable as intended.

“Did we raise tuition or fees higher than we should have? In hindsight, we probably did,” Driscoll said. “But at the time, it was a way to protect the core of the institution to keep our finances stronger. Who knew that it would be part of the problem going forward?”

There’s also the problem of perception. For decades, IUP has fought a reputation of not being academically rigorous. Some prospective students have dismissed the university because it’s a state school. And, things like being ranked the number-one party school in America by the Wall Street Journal last year continue to devalue any academic currency IUP has earned from its expert faculty, evolving facilities, and highly regarded programs.

“There wasn’t an event I was at this past fall where I wasn’t asked about [the party school ranking] by a student or a parent,” Hopkins said. “It reflects poorly on the academic reputation of the university. We have so many positive stories we could share, but unfortunately, people don’t always hear them.”

Unfinished Business

There is another significant component to IUP’s enrollment troubles. Going back at least a decade, roughly 3 of every 10 first-year undergraduates have chosen not to return for their second year.

“This is not out of line with national averages for a university like IUP,” Driscoll said. “But we can do better.”

IUP’s retention rate for the 2023-24 school year (71.5 percent) ranked seventh among what are now 10 State System entities. The bottom line is it was hurting IUP’s enrollment as much as demographics were.

In 2017, Driscoll commissioned a task force to investigate the causes of the retention problem. Paula Stossel, now IUP’s strategic advisor to the president for Student Success, was cochair of the committee, called the Task Force on Undergraduate Retention, and she said the group found no easy explanations.

“Finances are a big reason, and so are academics,” Stossel said. “Health is a big reason, and that’s mental health and physical health. Family is a reason. Some students left because they wanted to be closer to home. Some students were homesick, and some left because they just didn’t feel like they belonged here.”

Additionally, many students were coming to college unprepared, which meant they started their academic journey behind the eight ball.

“The reality is there are students today who come to the university who 10 or 20 years ago may not have even considered coming to college, because they weren’t prepared for it,” said Tom Segar, IUP’s vice president for Student Affairs.

The Impact of Fewer Students

Declining enrollment means declining revenue, and losing 40 percent of its students over a decade left a multimillion-dollar hole in IUP’s budget.

When the State System was created in 1983, it relied mostly on taxpayers to provide Pennsylvania residents with affordable options for college. But in time, the funding model changed. Tuition now covers most of the schools’ operational costs, with the state appropriation level changing year to year, largely due to politics.

“There’s not enough money in Pennsylvania to get us to the midpoint in per-student funding,” Driscoll said. “We’re still at, or near, the bottom, because other states are raising the ante. But we can at least try to catch up and keep costs reasonable for families going forward.”

In 2019, the State System graded each of what were then 14 university entities on their financial health. Each school was assigned a color—green, yellow, orange, or red—signifying a financial rating ranging from good to bad. IUP was assigned orange, meaning it was functioning but in danger if it didn’t take immediate action.

And, some of those actions have been difficult.

The faculty, staff, and administration needed to be rightsized to reflect the lower enrollment, leading to a smaller workforce. The academic programs went under the microscope, as did the facilities.

“We’ve done some really painful things that I thought I would never have to do as president,” Driscoll said.

The State System required each school to submit a report annually that shows how it is addressing its financial challenges. New grades are given out every year based on these reports, and IUP has stayed in the orange, despite taking drastic steps to reduce spending.

“There is much more work to be done,” Fitzsimons said. “If we hadn’t taken the steps we’ve already taken, we’d be in the red. We’ve had to come up with permanent solutions.”

If IUP failed to address these shortcomings, the likely resolution would have been for the State System to step in and take control of the university, a dystopian future that would leave permanent scars.

“In other systems, they call it receivership,” Fitzsimons said. “They’ll take whatever measures are needed to intervene, and in my opinion, any decisions they would make aren’t as good as the ones we would make ourselves. We want to continue to make our own destiny.”

An Admissions tour stopped in Elkin Hall.

Working the Problem

Rather than sitting by and waiting for a rescue or continuing with old ways and hoping for different results, IUP is attacking the enrollment problem on several fronts. And, there is evidence of progress.

In 2020, members of IUP’s administration, faculty, and staff contributed to a new strategic plan with a priority of transforming “the culture at IUP to enhance the student experience by fostering exceptional student centeredness. Transformation will include reordering resources to ensure every student is engaged and can be successful at every point in their journey.”

As a blueprint, Driscoll introduced a list of presidential goals. First on the list, and most important, is to retain every student who comes to IUP. That means the university must fundamentally change the way it operates so student success is the priority. Although certain parts of the university—particularly many individual faculty and staff members—may have worked to that end already, it must become a common thread throughout the IUP fabric so that students feel supported and cared for.

* Integrated into Pennsylvania Western (PennWest) University in 2022

† Integrated into Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania in 2022

‡ Formed in 2022

§ Change during years operational between 2012 and 2023

Source: Pennsylvania’s State System of Higher Education,

IUP Office of Institutional Research, Planning, and Assessment

“We can’t build this future by a few people sitting in a room coming up with brilliant ideas,” Driscoll said. “We need to own this as an organization. This is about a culture change.”

After receiving input from groups across campus, the University Planning Committee proposed the installation of a new student success infrastructure, putting people and offices in place to help students start and continue their IUP journey without roadblocks. Established in the summer of 2023, the infrastructure has 18 navigators as its most visible component. These full-time staff members have been trained in the best ways to help students, and they work every day to keep them on track academically, emotionally, socially, and in whatever manner they need.

Another factor that has helped is IUP’s commitment to affordability. In 2022, the university announced its Tuition Affordability Plan, which included a return to the flat tuition model and resulted in a nearly 20 percent cost reduction for undergraduates. Because of that and other measures—the State System has held tuition steady and IUP has frozen housing and dining costs for the past six years—the cost for in-state students to attend IUP today is only about $100 more than it was in 2016.

The early returns show that the plan is working. The 2023-24 enrollment of 9,254 students is an increase of 422, the most gained by any school in the State System and IUP’s first increase in 11 years. At the start of the spring semester, IUP’s fall-to-spring retention rate for first-year undergraduates was 90.1 percent, its highest since 2010.

One of the seven presidential goals is to grow IUP’s reputation, while another is to educate new student groups. IUP’s proposed college of osteopathic medicine, tentatively scheduled to open in fall 2027, would address both those goals. Although opening a medical school is a costly proposition, IUP is working to ensure the funding will come from new sources.

“We are not relying on our existing budget to stand up the college of medicine, and that’s something President Driscoll is committed to,” Fitzsimons said. “We don’t want to take away from what we normally do. We won’t be using the regular operating budget.”

Opening a college of osteopathic medicine is expected to help IUP’s enrollment in other ways. The college would be the first of its kind at a public university in Pennsylvania, enabling it to provide more affordable medical training. It would also raise IUP’s academic profile, helping it stand apart from similar State System schools, and would possibly attract students from other states.

While projections show that a significant drop in the number of high school seniors is looming, the work IUP is doing now has helped change the culture and stabilize enrollment so that the university is strong enough to withstand more challenges.

“I’m very confident that we can do it,” Fitzsimons said. “There is a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Every student—new or continuing—is assigned a navigator, like Marcia Mpfumo Briscoe ’09.