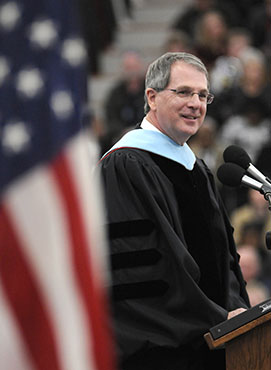

The following address was given by Ben Rafoth, a faculty member in the English Department and IUP's 2010-2011 University Professor, during the midyear undergraduate Commencement ceremony Sunday, December 19, 2010, in Memorial Field House.See video coverage of Rafoth's keynote speech on YouTube.

Congratulations, Class of 2010. Life tries to pull you in a million different directions, but a college education changes you. It forces you to look inside yourself and ask, "What is my oxygen?" It challenges you to find what is so important to you that you can't live without it.

But how do we decide what's most important?

The answer is different for everyone, and memories are the key.

Over the past several weeks, I interviewed twenty seniors about IUP people, places, and events that helped them to discover what's important to them. Some expressed the worry that, as Yogi Berra might have said, the future ain't what it used to be. Others told me about disappointments and rewards, about how blessed they feel, and what they hope to give back. They spoke about the knife-edge of being on their own and about dreams that are still within reach. Their stories are sometimes silly, sad, and inspiring. They remembered times when they felt simply and beautifullyhappy.

I call these "cling memories" because they stay with you for a long time, and the reason why they stay with you is the purpose of my speech. You see, I believe that college creates cling memories because we need them. Maybe not for now, but down the road, when big obstacles test us and we have to decide what is most important in our lives, when we have no choice but to arrange our priorities, when questions like, "How should I live my life?" and, "What am I good at?" are no longer academic exercises, but for real. I believe that your cling memories from IUP will help you get through life.

I had never met most of the seniors I talked to, but I felt lucky to get to know them. They gave me permission to share their stories.

Let me begin with two seniors who remembered random acts of silliness.

Aaron Chiang still drives his nine-year-old black Toyota. "I've had fourteen people in it, cruising for food at 3:00 a.m. We'd drive around Indiana three or four times and always end up at Eat'n Park. One time, we were after the best view of Indiana, so we drove up the hill to St. Bernard's Church. I gazed down upon on the town and then I looked up at the white sky, and all of a sudden, I saw these strange, black, stringy things moving in the air. At first I thought they were bugs or pollution or something, but they were IN MY EYES. And then my friends said to me, Aaron, dude, those are floaters, everybody has them.'"

I talked to Meredith Bird, who grew up in small towns in Virginia and New York and has five brothers and sisters. She reminisced about freshman year in Foster dining hall and pushing tables together because the dinner group kept growing. "It was a time when you could be carefree, even juvenile," Meredith said. "We would do silly stuff like steal each other's hats, race to the door, or hide behind a corner so we could jump out and scare one another. We were SUCH FRESHMEN!"

Freshmen are not freshmen for long. Some of the seniors were grateful for eye-opening experiences.

Rose Catlos is a native of Indiana with bright green eyes who met her two best friends at orientation. "They helped me to see the world in a different way. One of them took me to an anti-war protest, and I couldn't believe the people I saw. There were hippie-types, but also people in suits, kids, and older people, and many got arrested. I realized how passionate people can be about things they really believe in. It was an experience I never would have had on my own."

Ryan Hancharik grew up in Greensburg and applied only to IUP. When he got here he did a few dumb things, but he decided he was the sort of person who likes to get things done. He landed an internship at the Hershey Country Club and started two businesses. "I've found my happy place," he said.

Ray Edwards has short blond hair and is training for a marathon. We stood on the Sutton Hall steps, where he said he sometimes likes to sit by himself late at night. "The globes on the light posts get all misty, and in the winter on a clear night you can look up and see Orion and his sword.

"When Cornel West spoke in Eberly Auditorium," Ray said, "he helped me to understand why race matters. As a white guy, I used to think if I lived right and did my part, race was not an issue. But IUP is more like the world as it is today than where I grew up. One of my roommates was a Haitian from Harrisburg, and another was a banjo playing sailor from Allentown. IUP teaches you the way other people see the world. When I went to India this year, I met a kid my age whose main ambition in life was to finish work each day and then go home and take care of his aging parents. Most guys I know look for ways to get away from their parents. But this guy I met in India, he was twenty-one, and that's what he wanted to do more than anything else in life."

Some seniors remembered the support they've received from family and friends, or of making it on their own.

I met Emily Trenny at "her" table in the first floor of the library near the Government Documents. Emily told me she will never forget November 4, 2008it was about 11:30 at night, and CNN had just announced that Barack Obama had won the election. "The campus went wild," Emily recalled. "A wall of students headed into the Oak Grove, and I was pushed into the celebration. It continued late into the night. People were climbing the trees in the Oak Grove and jumping into leaf piles. I'll never forget that." She paused. "This campus never sleeps. Someone's always out and around."

Reflecting on how she got through college, Emily said she would tell her mom and dad "thank you." "They always supported me and pushed me even when I hated it. I love them for everything. I'm a little scared to go out on my own."

Danielle Graves grew up in Philly and figured, if she came to Indiana, no one would come after her out here.

Danielle was valedictorian of her high school, and she was heartbroken when she got her first grades freshman year. Things went downhill after that. College was different. It took a while, but then Danielle pulled it together with help from friends, but mostly she figured it out on her own, just as her mom told her she'd have to, before she died in 2005. "Are you excited about your future?" I asked. She grew a big smile and said, "I can't wait to move on and have a new start. But I don't plan to change much about myself, because I think I'm a good person to begin with."

I talked to seniors who recalled people who left a lasting impression on them.

Shane Conrad remembers having a bunch of friends when he was a freshman. "One girl, Sara, she hugged everybody. She hugged us so much that we would all huddle together so she could hug us all at once and we wouldn't waste time. But as the years went by, some of the friends fell awaygrades, drugs, or they just moved on.

"I've had some incredibly smart teachers," Shane said. "One of my professors expects so much of youyou find you can do things you never thought you could. She doesn't let you slack. Another professor has been like a friend to me. It's meant a lot."

You've seen them running on campus at 6:00 a.m., and you see them in uniform and carrying the flag to remind us that, for all its flaws, we live in a pretty great country. A few weeks ago, I spoke with ROTC cadets Richard Recordon, Michael D'Amico, and Charles Ruffo. They'll be commissioned as Army officers here today. Recordon, D'Amico, and RuffoI'll call them by their last names because that's the way they talkare tough, gentle, funny, smart, and in awesome physical shape. I asked them if there's anything they are afraid of.

One said spiders. Another said heights. "Heights?" I asked, thinking about Army airplanes and helicopters. "I'm okay with climbing towers, roller coasters, stuff like that," he said. "Just please, God, don't put me on a Ferris wheel." I told him he probably wouldn't have to worry about Ferris wheels in the Army.

When I asked whom they admire, all three named their lieutenant colonel. "He's with us," they said. "Whatever we're doing, in the cold, wet, mud, he's a part of it."

I asked them about the presentation of colors in graduation ceremonies like this and what we should be thinking about when the cadets march down the aisle, carrying the flag. Recordon said: "The handling of the flag, that shows respect for everybody in uniform. You can take the flag for granted, or not. But it's your flag."

As a teacher, you have to try to get to know your students because when you stand at the front of the class, usually you have no idea of the complex lives behind the bright faces.

Julie Vavreck is president of Mortar Board and captain of the IUP Rifle Club. We met at the shooting range, and she showed me her rifle. It's pink and green, and she wins a lot of tournaments with it.

"I've brought my sorority sisters here to the shooting range. We start out shooting at paper targets, but mostly we like to shoot at fun stuff like pennies, paint balls, little rubber toys, credit cards, and textbooks. Textbooks are good because you can see how far the bullet goes in. That's a lesson in itself," she quipped.

"In December of my freshman year, I did something radical," Julie said. "When my dog Brandy died, I got a tattoo on my lower back to remember him. It's a paw print. I am the first person in my family to ever get a tattoo, and when they found out, my parents flipped out. My dad couldn't even speak to me. My mom cried. Even my coach pulled me aside and said, Julie, that thing can be sanded off.'"

Then Julie looked straight at me. "Sand it off?!" Julie exclaimed. "No one's going to sand off my Brandy's paw print!"

Julie wants to leave everything she's involved in a little better than when she found it. Her goal is to help people with disabilities learn to do the things most people take for granted, like going to the grocery store, or riding on a bus.

Maria Kaminski grew up in Philadelphia and then moved to Indiana to go to college and be some place with after-school activities for her two children. Her favorite place is the planetarium in Weyandt Hall. "I'm working two jobs and going to school, and I've had some challenges in my life," Maria said.

"We decided to get married after I was diagnosed with cancer," she began. "I had taken care of my mother for seven years during her battle. I didn't want to put him through that, and so I told him goodbye. But he wouldn't hear it. He had fought in Iraq and said he was not about to let my diagnosis beat us. Twelve days before our wedding day, my fianc was killed in an auto accident. He had survived Iraq. I've survived cancer. But just like that, he was gone. We talked for six minutes before he died."

Maria and I had planned to meet in the planetarium, but the doors were locked, so we wandered around Weyandt Hall until we found a place to talk. I sensed in Maria the inner strength of someone whose memories speak to her every day.

"Being an older student, I didn't think I would fit in with all of the young people on campus. I mean, when I graduated from high school, there were still nine planets!" she laughed.

"But students here accepted me immediately," she said. "Some of my professors have been the most compassionate people ever. When I was having chemo, one of my professors fed me. They wanted me to succeed. I feel like IUP is my family, even if I won't be around for most of the class reunions."

"Hardship teaches you a lot," she said, "and that is something I've been able to pass along to my kids. You learn to save money by turning the lights off. I made my daughter's prom dress. That sort of thing."

Why the planetarium? I asked. Maria explained that she wrote a paper for one of her classes, and instead of using the word death, she wrote, "the other side of the moon." "That might be what got me started going to the planetarium," she said. "Last Tuesday, I spent my fianc's fiftieth birthday in the planetarium. If my life had gone smoothly, I don't know if I would have gone to college. Coming to IUP helped me leave another life behind. My degree is something I did for myself. And I have more friends now than I've had in my whole life."

Melody Thomas has lived with her parents and been a commuter for the past four years. She's a graphic artist and works two jobs. She has hazel eyes and has been accused of spreading extreme laughter and happiness.

Melody told me, "I want to go to graduate school and be a professor. But where I grew up, people would say, She's fooling herself into thinking she can do things she can't.' Maybe that's why I have a bad habit of not believing people when they tell me I'm good at something. But one of my professors said, Melody, you have grad school written all over you,' and my boss where I work on campus told me I'm good at what I do. That's when I decided I had a future."

I asked Melody: If the Oak Grove had a wall, like a Facebook wall, what would you write on it? She said, "I'd tell everybody, You're going to be OK.' We went to a good university and we have food and clothes. I'd write, You're going to be OK.'"

I asked Melody if maybe she was talking about herself. She said, "Yes, definitely."

When I began my remarks, I said it was important to look inside yourself to figure out what matters most, and that your memories of college would help you do that. Let me relate one final story that drives this point home.

Gerald Mensah left his family and came to Indiana from a small town in Nigeria, where he was born.

"When I started IUP, I had just come from Nigeria, and it was rough. There was culture shock, and I was young. My freshman year I learned things the hard way, like not to mix four kinds of soda together in the same glass when you go to the caf."

Gerald is twenty-seven years old and barely recognizes the person he was when he started IUP. "Acting crazy eventually caught up with me. It ruined my marriage, my job, and holidays. When I first came to IUP, I started off on the wrong foot, but that has changed. I decided that I wanted my family to be proud of me, and once I figured out how important that was, I became a different person. Really. That was it. I did not want to embarrass my family because they mean everything to me. My family tells me when I'm wrong, and I've needed that to set my life straight. I'm here now, in the U.S., but I don't want to forget where I came from, either. Remembering where you come from makes you who you are.

"As many complaints as I have about IUP," he said, "I'll really miss this place. It's been a privilege to go to school here. Not ivy league, not Big Ten, but I've gotten a great education at IUP."

Then he spoke slowly. "What I really learned at IUP was in and outside of class. I learned what's important to meto me. You can't put a price on that."

And there you have it, Class of 2010. Memories of college cling to you for the rest of your life because college is where you begin to discover what is important to you. As you wind your way through life's side streets, memories of IUP will appear in your rearview mirror, and they will be closer than they appear. Those memories are calling you back to a time when you laughed often and made friends easily, slept soundly, and worked like crazy. Those memories are calling you back to a time when you were enthusiastic and ambitious about your priorities. Bob Marley said, "You have to be someone." Down the road, when IUP memories flash in the mirror, remember that they're trying to tell you something, to hold on to what matters more to you than anything else in the world, just as you did in 2010, in a town called Indiana.

Good luck, seniors! And come back to visit!