Eileen Mountjoy

Among the shelves of solemn-looking, leather-bound record books stored at the R&P Coal Company's Church Street offices are several volumes dating to 1881, the year the firm was founded. These books, most still bearing a fine film of coal dust, sum up, in brief notes and columns of figures, clues to both the history of the company and of mining in Indiana County. One or two, stamped with dates from the turn of the century, have on their pages, in an elaborate handwriting of the kind no longer taught, the names of miners and a record of their employment over a period of several months.

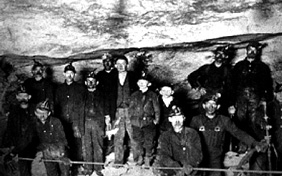

Many of the men named in the books are long forgotten, while others Left behind sons and grandsons who, in their turn, helped make Indiana County one of Pennsylvania's largest coal producers.Across from each man's name is written his particular job in or around the mines, and most, in these days of continuous mining machines and gigantic power plants, are as puzzling as words from another planet. Among the lists, the terms "spragger," "trapper," "dock boss," and many others stand out from the neatly lined sheets to baffle the modern reader. The unraveling of some of this mystery begins with a glimpse into a coal mine of a generation ago. Wearing a "Sunshine" lamp, which burned a paraffin-like substance, or later, a carbide lamp for illumination, the old-time miner worked in the equivalent of an underground city.

The "main entry," often compared to a main street, dominated the layout, while other entries were dug parallel to the main at regular intervals.These parallel entries were connected at right angles with cross entries somewhat like side streets. "Rooms," about 24 feet wide, were made at regular intervals. Many laborers were required in the preliminary stages, including a special "rock man" called in to blast down enough rock to attain the desired height in the main entry. The heights of the room was determined by the thickness of the coal seam which was, in Indiana, Jefferson and Armstrong counties, an average of 32" to the six feet found at Iselin and parts of Lucerne. The working surface in each room, called the "face," was advanced a few feet each day into the solid coal in the direction of the cross entries.

Before the advent of sophisticated machinery, men daily matched their strength almost single-handedly against a mass of coal hundreds of feet beneath the surface, broke it down into sizes suitable for handling, and loaded it into cars for transportation to the surface. From the beginning of commercial mining in our area in the late 19th century until the years just before World War Two, the digging of coal remained a skilled craft requiring the combined efforts of many men who performed a variety of jobs now made obsolete by modern technology. While engaged in his daily tasks, the working miner constantly used a vocabulary of job-related words not easily found in the standard referenceworks of libraries.

The retired miners of Indiana County, however, can answer our questions from a vast store of personal experience. Mainspring of the old-time mine was the "pick miner," and Alvie Lydick of Taylorsville vividly remembers the many hours he spent in that activity: "Each man, or usually two buddies, had a room of his own. We had to timber up our own place to support the roof, lay the track up the from for the coal cars, and bail the place out if it was full of water." Alvie also explains how the coal was "shot down" by hand with black pellet powder. While larger companies had compressed air "punching machines" to undercut the coal before shooting, Lydick remembers doing it the hard way: "If you were in low coal, you had to lay on your side, and with your pick, you made a V-shaped cut underneath the seam of coal so it would fall down cleanly after blasting. 'You also had to put short props of wood underneath, so it wouldn't fall on you," he emphasizes. "After the cut was made, we'd 'stamp' a little round place in the face with a pick, to make a pocket to hold the auger from slipping around. Then, we'd drill a long hole in the coal with the auger, very slowly and with a slant up towards the roof. "Next, the miner pulled the parings out to leave a nice smooth hole. Some men made a scraper out of iron, which helped to clear any loose material out of the drill hole. "Next, you'd roll up black powder into a tube of newspaper. How much to use depended on the coal. "If it seemed free from the roof, it didn't take so much. In non-gaseous mines, you could use black pellet powder, which was very inflammable. "But in a gassy mine, the men had to use an approved powder or approved dynamite sticks.

"When the drill hole and your powder were prepared, you took a tamping bar that had a copper end so that it wouldn't make sparks, and laid over top of a long copper needle. "The bar was used to push the powder to the back of the hole by pushing the end of the needle into the rolled-up newspaper that contained the powder charge. The needle was left in the hole, and the bar pulled out. "Then, actual tamping began, using the soft bottom clay for tamping material. "A lot of men used powder coal for tamping material, but that was really illegal, as coal is combustible. "When the hole was packed real tight, you'd pull the needle out, twisting it a little as you pulled, to make a nice smooth tunnel back to where the powder was. "After we pulled the needle out, we a used a fuse called a 'squib' which looked something like a drinking straw filled with powder. "When the fuse was inserted into the end of the drill hole, you'd yell 'Fire"! three times to warn everyone, light the squib, and run!"

The method of shooting coal described by Alvie Lydick continued well into the thirties, when mining laws insisted on the employment of specially-trained and licensed "shot-firers," who, after the coal was cut with machines and the holes made with electric drills, set off the shots with a charge from an electric battery.

After shooting, the buddies loaded the coal into the wooden coal cars by hand. In low coal, this involved an ingenious techniques in which the miner threw the shovel full of coal upward, where it bounced off the roof and into the car several inches below. In the days of over-production, loading was often made more difficult by industrial consumers' demands for only the largest lumps of coal, sometimes bigger than the span of a man's arms.

Once loaded, the coal was usually taken to the surface by one of two methods. The R&P's old Rochester mine, one mile west of DuBois, was acquired from the Bell, Lewis and Yates Mining Company in 1896. The Rochester mine, originally opened in 1877, was famous for its double track rope-haulage system which used four drums powered by two large steam engines. This was a very efficient but complicated means of hauling coal from the mine workings to the tipple and returning the empty cars underground. Although one of the marvels of the rope-haulage system was the fact that only one man was needed at the controls, the services of many other men were required to keep production running smoothly.

Andy Haggerty of Indiana, who retired in 1970, is cited by the R&P officials as one of the company's best supervisors. As a man whose mining career spans many years, Andy speaks from first-hand experience: "That old rope-haulage was so efficient, especially on a slope, that we still used it out at Tide until we closed down in the forties." From the old record books, Haggerty can pick out one or two jobs associated with this method. "On rope haulage, we had to have 'roller tenders.' You had to keep the rope from dragging on the track, and they had big rollers for the rope to ride on. The roller tenders kept the rollers well greased. "And you had to have an outside engineer to run the whole system from his place in the hoist house."

Another method of haulage entailed the use of small locomotives called "motors" run by electricity from trolley wires suspended from the roof. "The company employed 'wiremen' to hand the cables," Andy says, "and with each advancement of the mine, the wires had to be extended too. This could be quite dangerous considering that the wires held 250 volts."

The man who ran the motor was. of course, called the motorman. The spragger was his helper. The name "spragger" may be traced to the days before mine cars were equipped with brakes. To stop the cars, the brakemen carried "sprags," short pieces of wood about 18" long and 2" thick, which were jammed in through the spokes of the wheels. "The spragger also had to jump off the motor, disconnect the empty cars and put them near the rooms for the men to load," Andy says. "Then he'd connect the loaded cars to the motor to be pulled out to the side tracks to await haulage to the tipple by a larger locomotive. "He was also responsible for making sure the switches were working right and that the track was clear. "Sometimes, the spragger was called a 'trip rider.'

Haggerty remembers one particular spragger with respect: "It was also the duty of the spragger to run ahead of the motor and open the ventilation doors for the motorman. "There was one guy at Ernest who spragged for Vincent "Runt" O'Hara. The men nicknamed the fellow "Horseshoe" because he was such a good horseshoe pitcher. "This man could run like a rabbit. He would run alongside the motor, open the, door and hop back on the trip as it went by. "Then the motorman would knock off the latch and the door would close behind them. Runt never had to waste any time stopping the motor to wait for doors to open when Horseshoe was on the job."

O'Hara still remembers his spragger with affection. "This guy was only about five feet tall, but he could run faster than the motor. "He was a terrific spragger; one of the best. Together, we really got the coal out."

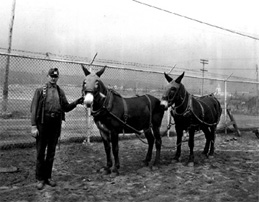

To the men working in smaller "country-bank" mines or if no electricity was routed out to the cross entries, spraggers and motormen were replaced or supplemented by four-footed haulage. Benjamin Trunzo, of Beyer, recalls his experiences:

At Sagamore, we had big motors to haul coal, but we used mules to haul coal from the rooms to the main heading. For a while, I worked as barn boss in Sagamore's underground mule barn in mine #13. We kept the mules underground to save time as it would have taken over An hour to drive the mules from outside to the face. It just looked like a regular barn in there. We had 10 mules; two to a stall. All hay and grain was taken in by mine cars and we had to have; iron doors on the barn to keep the mine rats out of the mules' feed.

Some mules stayed underground all the time unless they were taken outside for new shoes. People always thought that mules kept underground went blind, but that isn't true. When we took them outside for any reason, though, we'd keep then. blindfolded for a while and let them get used to the light gradually.

A lot of men were afraid to drive the mules because they could reach around and bite or kick you. And some were so smart they'd stand real still while you harnessed them, and hooked the cars to the singletree. Then with one quick motion, they'd lift a hind hoof and unhook the cars and just stand there and grin at you or run off. Part of my job as barn boss was to take the green mules into the mines to try them out. I'd put lines on them and see if they'd obey my commands. If they acted real mean or wouldn't work, we'd send them back. Some of the-mules were real good workers and the fellows would make pets out of them and feed them tobacco and pieces of bread. I particularly remember Topsy, Tom, Skip and Daisy.

Once at Sagamore we had a driver named Old Man Fulton who really liked the mules. This fellow could throw his voice. He'd pretend to be a mule, and make the animal say, 'Hey, Hurry up in there, I'm loaded and ready to go!' But if the mules acted up or wouldn't pull, some men would get real mean and beat the mules with whatever they had handy. After all, the miners were paid by the ton and had to get that coal out.

Merle Craig of Indiana remembers driving a mule in the Puxsiana mine near West Lebanon:

I worked there on weekends and summer vacations while I was in high school. Now, I was a pretty ambitious kid ordinarily, but one day I found myself wondering if it might not be easier to drive the mule than it was shoveling coal out of six inches of water. So one day when the regular driver got drunk and didn't show up for work, I got my chance. You had to drive the mule to each room, and pull the cars out to the main: track for the motor to pick up. Nell, this mule was like most mules; he started or stopped only when he wanted to. And there were no brakes on those cars. You had to stop them by throwing a sprag into the spokes of the wheel. If the car got off the track, there you were in the dark all alone, and you were expected to get a car loaded with a ton of coal back on the track. And the mule was no help at all in that situation! I decided that driving the mule was much worse than shoveling coal, although I stuck the day out.

Spraggers and motormen were also an unknown luxury to young boys who worked in old-time mines as doorboys, sometimes known as "trappers." Trappers, from the earliest days of the industry until the World War I era, were among the lowest-paid underground workers, usually averaging around $1.60 per day. According to a state law enacted in 1915, no boy under 16 could be employed in a coal mine, but Ben Trunzo went to work as a trapper boy when he was 14:

I didn't want my dad to know I was working; he thought I was too young. So I got a job as a doorboy. I worked from 7:30 in the morning until 3:30. That way, I was home and cleaned up before he got there. My dad didn't find out for quite a while because he worked twelve hours a day at Sagamore drying sand for the motors to use -- sand was sprinkled on the rails to help gain traction going up or down a grade. Trappers were responsible for the opening and closing of underground ventilation doors. In those old mines, they had a system of doors between sections to direct the flow of air. Air was supposed to go up the main haulage and back to the fan. So a trapper sat all day by his door with an oil lamp on his cap. There was a 'manhole' -- a shelter hole in the wall by the track. The motorman would blink his motor light at me, and I'd throw the switch and open the door for him. Then, I'd jump into the manway until he was past, and run out and close the door. A trip would come along about every hour. Was I bored or lonely? Well, it was my job.

In spite of his many hours spent underground, however, Ben took advantage of the schooling available to him, and had the chance to go to the Indiana Normal School and become a teacher. Instead, he chose to remain in the mines and eventually necessary certificates to attain the position of mine boss.

Then as now, adequate ventilation of the mines was one of the most important safety factors, and in addition to doorboys, many other men were employed to keep the air flowing freely. While in the earliest days of mining history, fans were used to blow fresh air into the mines, mining engineers soon discovered that this method only served to force explosive gases back into the workings. Merle Craig also adds that "at one time, some companies experimented with huge furnace placed outside a separate air shaft to draw out bad air from inside the mines."

As mining methods progressed, however, trained corps of vent men, bratticemen, and masons built underground airways kept flowing by huge fans housed outside the mines in brick shelters. As an individual mine attained greater proportions, specially designed air shafts were sunk to provide additional oxygen.

While many boys entered the mines as doorboys, most went in with their fathers to learn their mining skills from the best teacher available.

"One of the reasons men took their boys into the mines," says Ben Trunzo, "was to get more cars to load. A man alone could get only four or five cars a day, but if you had a son with you, you might get ten or even twelve.

Trunzo stresses the importance of going into the mines with one's own father or older brother:

When I started loading my dad was still making so much money outside drying sand that he hated to quit, but he did so that he could take me in himself. But after a short time, he broke his collarbone in an accident, and he was finished. So I started going in with an old man I knew. But do you know, that old guy cheated me something awful! If we loaded ten cars together, he would put his checks on six or seven of them. If we loaded nine, he'd leave me four. He says, 'But I'm an old man'.

After a while, Jake King, the superintendent, felt sorry for me, and even though I was only sixteen, they gave me a room of my own, even though you were supposed to have at least a year's experience at the face. But the boss told me, 'If you see two lamps coming, you'll know I have the mine inspector coming with me, so you run out into the crosscut and pretend you're looking for your pick or something.' I did real well for myself and loaded six cars a day.

Merle Craig also emphasizes the validity of the father-son tradition in the mines:

Was I scared the first time I went underground? Of course I was. On my very first day, my dad took me in with him to remove some of the pillars in a finished room in my grandfather's mine. Now pulling pillars is very dangerous work and usually reserved for experienced men. This job entailed knocking down the pillars of coal left in each room to help support the roof while the men were working in it. After all available coal was taken out of the seam in that place, the pillars were pulled one by one and that coal loaded out. By the time you were done, the roof was held up only by the timers.

Well that day, we had so many supports to remove that my dad couldn't understand why the room hadn't caved in already. We kept at that job for a week or so. The roof was so bad by when that I could hear the coal cracking and as the ribs started to buckle, lumps began to shoot across the room. The timbers were splitting the crumbling all around us and the whole place was rumbling like thunder, I kept saying to my dad, who was working very calmly with a pick and shovel, 'Dad, don't you think we'd better get out of here" Finally, just as I thought I couldn't stand it any longer, he got up, turned to me and announced: 'Well, I guess we'd better leave.' Just as we got to the main heading, the whole thing let loose. There was enough air pressure from the fall to nearly knock us over out in the main entry. But I trusted my dad, who was a very experienced miner and could tell from the sounds exactly when the roof would fall.

Ultimately, the hard-won coal, dragged out to the daylight by mule, rope or motor haulage, found its way to the tipple. There, another battalion of workers prepared it for shipment to factories, iron foundries, or for further processing as coke. Most of the group of outside workers were classified as "company men," who were paid by the day, as opposed to the miners who worked on a tonnage basis. The most important of these are easily picked out from the old record books: "The 'dock boss'," says Andy Haggerty, "checked the outcoming cars for dirty coal. If the dock boss discovered two or three buckets of slate among the coal, he'd give that miner a couple days off, without pay of course."

The weighboss, another company man, then weighed the coal and credited the tonnage to the man whose name coincided with the number of the small metal "check'' hung on the side of the car. Later, a union-hired checkweighman assisted with this job. In some mines, a "check boy" collected the checks and replaced them on pegboard for the miners to claim the next working day. After weighing, the loaded cars were pulled up into the tipple and "tipped" over onto a slowly moving conveyor. In the days before cleaning plants, "boney pickers" labored inside the tipple to remove by hand small pieces of slate, rock and sulphur missed by the dock boss." This job," observes Merle Craig, "paid so little that usually young boys and older men performed this task. "Also, it sometimes attracted a certain unambitious class of men who required only enough money to keep themselves in liquor. "The term 'boney picker' came to be used as slang to denote a person who is lazy." Before elaborate conveyor systems, the refuse set aside by the boney pickers were taken out to the dump by another employee called a "slate wheeler" or "rock larryman." After "picking", Andy Haggerty continues, "the railroad cars, called 'flats,' were swept out by the 'flat cleaner,' and pushed under the tipple by the 'car dropper' to be loaded with clean coal."

At some old tipples, "they had as many as five tracks underneath, one each for 'run of mine' coal -- that means just as the coal comes from the mine after being cleaned -- and four other flats waiting to be filled with different sizes: slack, nut, egg, and lump. "In another step before cars were sent to their destinations, the "trimmer" went to work to level off the cars neatly in anticipation of a long and bumpy railroad ride. Of all company men, the "fireboss" carried one of the heaviest burdens of responsibility. "Each day before he went into the mine," explains Andy Haggerty, who performed this task countless times, "he'd check a barometer kept in the lamp house.

"If the barometer fell, he'd know that gas was probably liberating freely underground, as outside barometric pressure affected conditions in the mine. "Then, three hours before the start of each shift, the fireboss had to inspect each working place and all adjacent places in the mine with an approved flame safety lamp. "The flame safety lamp was held up close to the roof, and if the flame inside elongated, there was gas present. "You had to be real careful how you pulled the lamp back down. If you jerked it suddenly, the flame could burst through the protective gauze and cause an explosion.

"As each place passed his inspection, the fireboss chalked the date and his initials on each working place in the mine. And after he got outside, he had to sign a book reporting that the mine was in a safe condition. "If he found gas, then warning signs had to be put up across each entrance, working place, or other dangerous section of the mine, and the men kept out until the mine was safe."Another job the fireboss did was to check for bad roof. "He'd test it -- 'sound the roof' -- with a special brass-tipped stick, and if it sounded "drummy", that meant the strata was separating. Then he'd send for the timbermen, who would come in and set more props.

"A real good fireboss could hold his fingers against the roof as he sounded it and tell whether it was four inches or three feet thick, and just what king of condition it was in. "In the real old days, before the fireboss," Andy adds, " there was a fellow they called a 'fireman.' "This man also went into the mines early to check for gas, but if he found any, he'd 'brush' it away with his jacket, or burn it out with his carbide lamp! "That horrifies us today but I guess it worked well enough if the gas in very small amounts." Other company men and supervisors included a track boss, who directed the laying of track up the main haulage. Track-laying, of the utmost importance in the removal of coal from underground to the surface, was often complicated by the "heaving of the bottom." "This," says Haggerty, "means that sometimes the floor of the mines actually buckles up, caused by a settling of rock strata."

When the bottom heaved, many sections of track were often twisted free from the floor of the mine, and needed immediate repairs. "Another job that track boss did was to lay connections, and keep the bolts tight and well bonded for the motor to run on." As in the early days, a foreman remained in charge of all the men engaged in various occupations underground. According to a state law enacted in 1915, applicants for certificates of qualification as mine foremen and assistant mine foremen had to be "citizens of the U.S., of good moral character and known temperate habits at least 23 years of age . . . and able to read and write the English language intelligently." Mine foremen, after passing tests given by a Board of Examiners undertook an awesome list of responsibilities.

Duties of the foreman included: "charge of inside workings and inside employees, see that the fireboss has left his mark in places examined, keep watch over ventilating apparatus, timbering and drainage, examine each working place daily, remove all dangers reported to him, and to see that the working places are kept free from water." "To help him," says Andy Haggerty, "the foreman had several assistants. "When I went to Ernest as a foreman in 1938, there were 1,275 men working there, and I had 52 assistants. "It was as though the foreman was a sheriff, and the assistants were deputies. "The foreman had to see that the law was carried out, and the assistants helped him. And over everybody in the mine was the superintendent. "Now in the old days, many of the superintendents didn't go underground very much, but as the mines mechanized, the superintendent had to spend more and more time supervising operations at the face." With the design and manufacture of mining machinery, methods of operation gradually changed, and new jobs were created within the coal industry.

The first machines commonly used underground were the early cutting machines intended to replace the miner's pick. "The first cutting machines, "Andy Haggerty explains, "were run by compressed air, and later by electricity. The men who ran them were called 'cutters' and they had to have an assistant who was called a 'scraper.' "Those old machines shot back a lot of powdered coal -- we called it 'bug dust', -- and the scraper was responsible for clearing all that away, or the machine wouldn't run. "On some models, the scraper also had to set up the jacks for the cable to anchor on the cutting machine." Mechanical loading devices were installed in a mine in Illinois in the 1890s and mining from 1910 to 1920 was marked by a slow growth of conveyor mining based on factory methods of the era. In spite of a variety of early-model mining machines available to large operations, however, handcutting the loading remained a vital aspect of the coal industry until the late thirties.

Mechanical mining, while it eventually freed the miner from the drudgery of pick and shovel, created many changes in his traditional methods of digging and transporting coal. Instead of two buddies in a room, for example, as many as six men sometimes worked together shoveling coal into a "face conveyor" for removal to the surface. In that case, "piecework" and payment based on individual tonnage was replaced by daily wages.

Today, the visitor to a large mining operation will search in vain for blacksmiths and doorboys, and company payrolls list no cutters or scrapers. Any engineer hired in 1979 is likely to be a graduate of a university rather than the man behind the controls of a rope-haulage system. As we look back at the history of mining in Indiana County, it is perhaps difficult to feel nostalgia for hours of shoveling coal out of six inches of water, or battling with cantankerous mules 300 feet underground. There are in our community, however, many members of a generation of skilled workers who proudly remember the satisfaction of individual achievement -when coal was mined by hand.