Select Readings Compiled by Mildred Allen Beik

Translations by Mildred Allen Beik, with assistance from Jitka Hurych and Alan Cienki. Courtesy of the Immigration History Research Center, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota.

On April 2, 1906, as many as 5,000 Windber-area miners publicly demonstrated their desire to become members of the United Mine Workers of America when they joined an orderly parade of the district's union miners through town. Their fellow miners had come to Windber to call upon them to join the union themselves and support the national organization's collective efforts and current strike.

Their conscious decision to join the union was an important one that, once taken, they knew would inevitably and immediately commit them to going out on strike against their adamant, antiunion employer, the Berwind-White Coal Mining Company. They eagerly and quickly made this decision. In the process, this large group of primarily immigrant miners--Slovaks, Hungarians, Italians, Poles, Carpatho- Rusyns-- simultaneously defied the coal company and the public's ethnic stereotypes. New immigrants were neither docile nor disinterested in the American labor movement.

Ever since the founding of Windber and the opening of the mines, Berwind-White's miners had had many grievances both at the workplace and in the community-at-large. The lack of checkweighmen, indeed the company's weights and weighing system which they considered grossly dishonest, along with the compulsory company-store system and arbitrary dismissals, were the specific grievances that they cited most frequently, but they mentioned many others. Most of all, they disliked the company's autocratic rule, the lack of civil liberties and democratic rights that they experienced in a company town in a state known for the Liberty Bell and Revolutionary fervor, in a country that prided itself on its legacy of freedoms. Yet, neither immigrant nor American-born miners had any voice whatsoever in major decisions that affected their lives at work or in the local community-at-large. For this reason, to the ordinary miner and members of his family, unionization always meant far more than higher wages or solutions to specific grievances, although these were important, too.

Readers can learn more about the ongoing grievances and specific struggles of Windber-area miners in the list of works at the end of this pamphlet. This short brochure is only a brief introduction to the aspirations and participation of these miners in the 1906 strike for union, one of the most significant happenings in 100 years of the town's history. Its purpose is to make readily available a few select rare documents about the aspirations and participation of these miners in an important strike which received prominent, and often scandalous, national attention. The occurrence of the local strike and its effectiveness, the leading role and mass participation in it by an immigrant work force, a massacre of four people by the coal company's hired guards, and the armed occupation of the town by the state police were spectacular instances of overt class conflict in a company-town setting in industrial America.

Given the prevailing national and regional climate of nativist prejudice against new immigrants and the realities of corporate power in 1906, from the start of the strike, Windber's foreign-speaking miners were at a decided disadvantage in making their case known to the general public. Yet they were creative. That they viewed unionization as a means to gain greater freedom and control over their lives, basic economic and democratic rights, and the end of what they themselves considered enslavement, is clear in the following letter from Martin Smolko, a Slovak miner in Scalp Level, Pa. He wrote this letter in the early days of the strike to warn his fellow countrymen of the Berwind-White Coal Mining Company's attempts to mislead immigrants and recruit scabs to break the strike. His quotation of the motto, "All for One and One for All," at the end of his letter suggests that he was already familiar with the Knights of Labor, a labor organization that preceded the United Mine Workers. Slovk v Amerike was one of the most popular Slovak newspapers at that time. Although most immigrant miners were literate in their native languages, they usually knew little English, especially at first. In any case, like Smolko, they naturally preferred to communicate with their fellow immigrants in their own native languages, which they eagerly did to support the effort to unionize.

Martin Smolko Letter

Published in Slovak v Amerike on April 17, 1906. Translated by Mildred Allen Beik.

Scalp Level, April 6

Dear Editor, Slovk v Amerike,

I am begging you please to publish a few words in our favorite workers' newspaper. We miners have flared up on strike. We are asking union recognition from the company. Until now we did not belong to the union and, therefore, the operators molded us according to their will--exploited and enslaved us, but now we see an opening and have recognized the advantage of unity. True, we are fighting such enslavement, for in general we have nothing to lose but something to gain from the undertaking. Now, however, with everything moving, we have wakened from our sleep and are fighting to be respected as free people and not slaves.

Therefore, we remind all brother Slovaks that various agents from around here are seducing scabs for the Windber region because here every miner's position is with the strike. Therefore, brothers, stand up like brave Slovak countrymen should. Remember the password (keep it in mind): All for one and one for all.

With respectful greetings, Martin Smolko

From April 2nd to April 16th, according to all available accounts, the strike in Windber was both effective and peaceful. On the 16th, Easter Monday, however, a series of events occurred that culminated in the massacre of three miners and a young boy that evening. Many others were wounded. Private armed guards hired earlier in the strike by Berwind-White (Tanney company detectives, often mistakenly called Pinkertons) had fired into a crowd of people and passersby assembled near the Windber jail. Immediately thereafter, at the company's request, the sheriff requested--and received--a contingent of troops from the state.

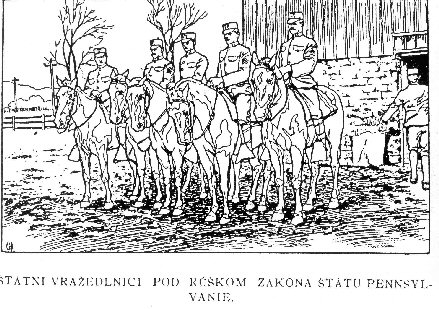

Troop "A" of the newly-formed Pennsylvania State Police quickly reached Windber from Greensburg by train, occupied the town, rode their horses through gatherings of more than two people whom they clubbed, and otherwise acted as strikebreakers. Although ostensibly stationed in Windber and elsewhere throughout the coal region in order to maintain "neutral" law and order, their real purpose--breaking the bituminous coal strike of 1906--rapidly became apparent. Moreover, the Pennsylvania State Police's own reports on its occupation of Windber indicate that these troops, exclusively American-born and English-speaking at this time, took great delight in forcefully subduing a largely immigrant working-class population of strikers. The above illustration depicts the Pennsylvania State Police during the Windber Strike of 1906 was published in Slovak v Amerike on June 12, 1906.

Immigrants learned of the antilabor, nativist actions of the Pennsylvania State Police in various ways. This photo, which appeared in a popular Slovak newspaper, was one of many that appeared in foreign-language newspapers that the immigrants read. Southern and eastern European miners and other workers popularly referred to these hated troops as "Cossacks" because they acted like the similarly repressive troops used by the czar against workers in Russia during the Revolution of 1905 and on other occasions. As the caption of this photo suggests, they also saw a close resemblance between the unjust laws of czarist Russia and the legal system of the state of Pennsylvania.

From April 16th on, the immigrant miners were at a great disadvantage in making known their side of the strike, the events of April 16th, the massacre itself. English-language and nativist newspapers quickly printed sensational and sometimes hysterical reports on the day's happenings, and they scathingly placed all responsibility for the company's massacre by its hired gunmen on stereotypical ignorant, foreign-born strikers, whom they now claimed had been violent, not at all peaceful, from the first day of the strike. The company had successfully made its version of events known to the Associated Press, and the country's leading newspapers had simply printed that version. The New York Times was one of many that put the company's narrative on the front page as a lead story.

Immigrants did what they could to tell their side of the story. The following letter is from Rev. Fr. Michael Balogh, who was priest at St. Mary's Byzantine Rite Catholic Church in Windber during the strike of 1906. He was also a speaker at the union meeting that day and an eyewitness to the massacre of Windber miners. He understood the importance of refuting the nativist, antilabor and often hysterical accounts that Berwind-White had promoted, and the Associated Press carried. Some of these reports had even been reprinted in ethnic newspapers! In order to correct such stories and accurately inform his fellow immigrants and Greek Catholic parishioners, he sent this letter to the official newspaper of the Greek Catholic Union and apparently to other publications.

Translation of "Oprava viesty podanej v zaleitosci kervprelievania v Windber, Pennsylvania."

A letter written by Reverend O. Michael Balogh's, April 26, 1906

Correction of the lead story on the matter of the massacre in Windber, Pennsylvania.

In the previous issue of The Messenger, we published a lead story from Johnstown, Pa., under the title, "The Situation of the Miners," about the terrible massacre which the sheriff committed with his deputies on the poor miners of Windber, Pennsylvania. We took the lead story from the English-language newspapers. On April 24th we met with His Eminence, O. Michael Balogh, the Greek Catholic Carpatho-Rusyn priest in Windber, Pa. He warned us that our description of this event did not correspond to the genuine situation of the matter there, and related to us in detail what had happened, and on the basis of this, we are publishing a new description of this unfortunate incident and indeed of its consequences, a description that His Eminence O. M. Balogh also published in the Slovak Daily.

On the afternoon of April 16th, the strikers held a huge meeting, at which meeting, in a field, the speakers were: Rev. Michael V. Balogh, the local Greek Catholic priest; Rev. Leo Stefl, the Roman Catholic Slovak priest; and James Saas, a Roman Catholic priest there; Mr. Paul Pachuta, curator of the Carpatho-Rusyn church and a union butcher.

The meeting opened about 3 o'clock in the afternoon. The first speaker was organizer Ginter, and he spoke in English and introduced Michael Balogh, the first other speaker, who spoke in Ruthenian to the people; the second speaker was Rev. Leo Stefl, who spoke in Czech; the third was Rev. Saas, who spoke in Polish; the fourth was Mr. Paul Pachuta, who spoke in the Ruthenian language and in Slovak.

All speakers expressed the same idea, that union miners should stay out on strike and behave peacefully and quietly, that they would not obtain anything through violence but only through a peaceful path within the boundaries of the law. The people acknowledged that, obeyed, and began dispersing. But the company was exceedingly angry at that, and also that the strikers had been peaceful and quiet for six weeks, and so it was looking for a reason, an incident, that through violence and with cause, they could incite a riot, and, therefore, under this pretext, see to it that there would come in the Pinkertons, among whom are two men who had fired on the people at Lattimer and Homestead. In order to have its own "action" as a pretext, it sent deputy McMullen as a messenger to the meeting. So he went there. The people told him that he had to leave, and everybody did so with quiet strength, although this man had no right to be there. Our youths wanted to throw him out, but he pulled out his own guns from both pockets and started shooting from them. This upset the people, and they surrounded him, and he began running away, shooting. When he came to Eighth Street, he ran into the house of Ellis Davis, a town official. The people were looking for him, and they wanted to catch him, but he hid in the cellar, and the crowd did something that wasn't necessary. They rushed into the house and smashed furniture. Because of this, several innocent people were caught, arrested, and taken away to jail. People followed those arrested with the good intention of bailing them out, but for some reason the burgess of the town didn't listen or allow that. People condemned this refusal with a lot of noise. In that moment, somebody from the crowd threw a brick on the jail's window, and at that point, the Pinkertons suddenly began to shoot and fired directly on a group of people who wanted to go on their way to church vespers.

The first victim was Stefan Popovic [Steve Popovich], A Carpatho-Rusyn who came from Vola, a place in Zempln province. He had a wife and three children here. He had no guilt of any kind at all. Also, it appears that he had his hands inside his pockets, and that near him and on him, no weapons were found. He was standing off to the side of the street in front of a store.

The second, Matus Tomen, from Moravia, had a wife and three children in the home country.

The third, Simeon Vojcek, a Pole from Galicia, had a wife and four children in the home country.

The fifth [fourth] was a 10-year old English boy Keerney [Curtis Kester].

There wasn't a weapon found on any of them. Besides these victims named above, there were 18 people wounded, shot through their the arms and legs, and they were all taken to the hospital.

But the worst of all is that the company has prevailed in the matter so far as not letting the arrested people go free unless they pay such exorbitant bail that it is difficult to collect. But some of the arrested have succeeded in obtaining freedom. In other ways, also, they twist things and indeed say that the strikers, the unionists, caused the riot, when exactly the opposite is true.

Even the Johnstown Democrat, reputed to be the fairest and most reliable English-language newspaper in the region, initially carried an inaccurate version of the events of April 16th. But it immediately sent investigators into the field and sensitively described the funerals of the victims of what it first called a "riot" but would later consider a "massacre." These funerals, attended by Windber-area miners and union officers in mass, were the largest funerals ever held to date in the town's history.

Johnstown Democrat, April 20, 1906, page 8:

Kester boy dies making fourth victim of riot. Largest Crowd Ever Seen at a Funeral in the Big Coal Town Turned Out for Dead Slain in Riot--Town Perfectly Quiet and Constabulary Patrols the Streets.

Windber, April 18. Curtis Kester, the 10-year old boy shot by the deputies here Monday night when the officers opened fire on a crowd which was gathered in front of the lockup, died this afternoon at the Windber hospital. This makes the fourth victim of the clash between the officers of the law and the throng clamoring for the release of eight men arrested at the riot on Eighth street. The shooting of the lad is universally deplored in Windber.

For the first time in the history of Windber a funeral at which 4,000 persons were present was held this morning and this afternoon. Two of the men shot Monday evening were buried this morning and one this afternoon.

The largest funeral of the three was that of Steve Popovich, which was held from the Greek Catholic church on Somerset avenue at 3 o'clock this afternoon. Almost every miner in the field, together with many other men and women, was present. Two bands were on hand and several foreign societies. Inside the church the last rites of the Greek Catholic church were said over the remains. The priest spoke a few words about the deceased and cautioned the people to be peaceful and to avoid trouble of any kind. The services were broken only by the sobs of the dead man's wife. One little daughter was present, but she was too young to understand her loss. The wife, however, could not be comforted. She was assisted into the church by a couple of friends of the dead man and sat with them during the services. As the services drew near their close and the priest and his assistants chanted the last of the ritual the grief of the poor woman became heart-breaking. At the grave, also, she was not to be comforted and many of those who saw the pitiful burial, where a strong man in his prime was laid away to rest before his time, were moved to tears.

Outside the church was the immense throng which could not gain admittance. The two bands were there and many of the foreign societies. Men talked in subdued tones about the incidents of the last few days. Everything was orderly until within a few minutes of the end of the services in the church. Then an Italian miner climbed onto a stump and commenced to harangue the crowd. What he said is unknown, but it bore on the troubles of the last few days. At times the speaker was at a loss for words in his own language and he cursed loudly in the English language.

The thousands of men on Somerset avenue were as quiet as the grave when the priest in his robes came from the church. The priest was bare headed and was clad in his robes of office. Back of him was a man with an uplifted cross of silver and two bearers of incense. All heads were bared until the clergy had taken their seats in the carriages and the body of the dead Popovich had been placed in the hearse. Then the march to the cemetery was commenced. The two bands, separated by hundreds of people, played mournful dirges. The marchers sang a chant of a sorrowful nature. The bells on the Greek church broke out into peals and the huge bell on the Catholic church on Graham avenue tolled.

Mike Toman was buried this morning. His funeral services were held in the Slavish Catholic church. The scenes at this funeral were similar to those seen later at the funeral of Popovich. There was a carriage back of the hearse and in this carriage was a woman whose grief was pitiful. The two bands played the Dead March from Saul and another dirge which is a favorite of the foreign workmen here.

Simon Novchek, the third man killed in the riot Monday evening, will be buried tomorrow morning.

William Curry of Lilly, president of sub-district No. 3, of the U. M. W. A., came to Windber this afternoon in company with Organizer James Purcell, who had been in the field before. Neither of the men would say a word regarding the local situation, stating that they came here merely to attend the funeral of the riot victims. During this afternoon they were closeted with several of the leaders of the local organization, but the result of this conference has been kept secret. Organizer Peter Lauer has gone to his home for a few days. Organizer Joseph Genter is still in Windber and attended both funerals today, heading the United Mine Workers in the parade.

Within a short time, the Johnstown Democrat concluded that there had been no justification for the indiscriminate shooting that had led to the Windber massacre. The Democrat's conclusions, along with a statement of support for the Windber strikers from the Windber priests were printed in the United Mine Workers Journal, April 26, 1906. A miner from Meyersdale sent the UMWJ the following letter:

Meyersdale, Pa., April 21, 1906

Editor United Mine Workers' Journal:

The garbled reports of a goodly portion of the subsidized press would have the reading public believe that the striking miners at Windber are a lawless and bloodthirsty set of men, indeed. Investigation, however, will not bear out such statements, for the men of Windber hold the laws of our country in as high esteem as the average citizen. We are asked to believe that the strikers are solely responsible for the lamentable outrage at Windber on Monday, April 16, when three men were shot down, apparently with the same grace as one would shoot a mad dog, and three others wounded, one of them a boy between ten and eleven years old, who has since died from the effects of his wounds, a total of four human lives, as part cost of daring to protest against the Berwind-White Coal Company's attempt to enslave men in a free country.

From what I could learn while at Windber (a few hours after the shooting) there certainly was no provocation for the extreme measures that were used, but I presume, that in this strike, as in many others of history, human lives, innocent or otherwise, weigh but little when placed in the balance with vested rights of corporations; their avaricious and rapacious appetites for gold, seemingly, must be satisfied regardless of who may suffer; human blood seems to be cheap when measured and gauged by the desires of the Berwind-White Coal Company.

I enclose herewith an editorial from the Johnstown Democrat, a metropolitan daily paper, that has had its representatives at Windber since the first day of the strike:

"The reports from Windber indicate that some one blundered. Let it be acknowledged that the strikers were as ugly as they have been pictured in the reports emanating from official sources. Let it be acknowledged that some of the strikers deserved shooting. But even then there remains no grounds upon which to condone the killing of innocent bystanders, of peaceable citizens and little children by deputies who fired at random into a retreating crowd, who shot without looking, not at particular men, but just at men in general. It is all very well to say that innocent men who get shot at riots had no business where they were. And yet it was luck or Providence that saved people in their homes from the fire of the deputies. Not only did bullets sing up the streets of Windber, pumped by reckless and frightened deputies from repeating rifles, but, flying wild, these bullets tore their way through houses many yards away; houses in which people certainly were dwelling peacefully."

It will be noticed that in no part of this statement does the Democrat say that the strikers gave cause for the murderous assault made on the people of Windber by these hirelings of Berwind-White, but it does say that the people were retreating when they shot to death; it says: "Let it be acknowledged that some of the strikers deserved shooting. But even then there remains no grounds upon which to condone the killing of innocent bystanders, of peaceable citizens and little children by deputies who fired at random into a retreating crowd, who shot without looking, not at particular men, but just at men in general."

And again, "The recent sad and lamentable action of certain Windber officials are very likely without justification."

This statement coming as it does from so prominent and trustworthy source (and, I might add, from an unbiased and impartial source), should be very significant, and in a measure, at least (if not conclusively) enable a thinking people to place the responsibility of this Windber outrage.

The verdict of the coroner's jury was that these Pinkertons shot these people while in the discharge of their duty. This part of the verdict we can not doubt, as that is their stock in trade; that is, as far as their duty to the Berwind-White Coal Company goes. But is there not higher duty, that even hirelings should be compelled to perform; is there not a way whereby the lives of people can have that protection the law is presumed to give?

As I stood and gazed into the silent faces of those murdered men at Windber I thought I could picture in their dead features an appeal to the living, not for vengeance, but for justice.

The blood of these Windber martyrs, together with those of Lattimer, Pana, and Virdin, and others, are all appealing to the living, for us to take the necessary steps that will make it impossible for murder in the name of the law.

My communication is already too lengthy to discuss these steps in detail, suffice it to say that I believe in ballots, not bullets, and I hope to see the day when the wage-worker will vote to the end that the appeals of those dead heroes will not be in vain.

Fraternally yours, H. Bousfield

The Berwind-White Coal Mining Company, which had not been able to defeat the strike at the local level, was greatly pleased with the repressive actions of the state. Captain John Borland informed the Pennsylvania State Police's Superintendent, John C. Groome: "The number of strikers was estimated at nearly four thousand and the Superintendent, of the Berwind-White Coal Company, was so well pleased with they way the situation was handled that he used every possible influence to have my men retained." [Borland to Groome, "Monthly Report. . . June 30th, 1906, Records of the Pennsylvania State Police, RG30, Pennsylvania State Archives, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pa.]

Windber-area miners and their families faced armed repression and many other obstacles in their efforts to organize. Before the inception of the national union's strike, UMWA President John Mitchell had won approval for a strike policy that authorized each district union to pursue separate negotiations and contracts instead of the national organization leading one uniform, national strategy. This decision, highly controversial at the time, reflected the national union leaders' perceptions that the coal companies' resources and powers were immense compared to those of organized labor. But this decision also meant that the efforts of local, previously, nonunionized, miners to organize would be very difficult. From the start of the strike, District 2 had had a fierce battle on its hand to maintain its organization against the newly formed Bituminous Coal Operators' Association which had declared its intention to destroy the union throughout the district that year. The result was that the hard-pressed District 2, U.M.W.A. organization could provide little financial relief to the distressed strikers in Windber.

Nonetheless, despite the massive repression, evictions, nativism, ongoing false reports to the press, company espionage, the systematic arrests of the local union officers for "arson" or other charges later dismissed, Windber miners did not end their strike for union. Immigrant and American miners responded creatively to the situation. Rather than become strikebreakers, many left town for other destinations in the U.S. or returned to their native countries. Annie Popovitch unsuccessfully sued—but did sue—the armed gunmen who had murdered her husband. Although times were hard, the miners who remained in Windber did not resume work until after the district had made a settlement of the strike in July, and all hope for securing a union at the Berwind-White mines had been lost. District 2, one of the last districts to settle the strike, had reluctantly negotiated contracts which saved what it could for its old organized locals, but it could not secure union recognition from Berwind-White and certain other hostile open shop companies. Lacking the funds needed to continue the local strike, Windber miners had to temporarily abandon their hopes for unionization, and all that meant to them.

Miners temporarily abandoned their unionization struggles but not the idea of union itself. The strike itself had been effective and costly to Berwind-White too. Strike participants might have found some comfort in the old labor saying "A lost strike is never lost," if only because it showed employers that workers would not endure endless exploitation forever, without protesting, and without exacting a heavy price of its own in return. Pragmatic miners would weigh their options carefully in the future. After 1906, those who remained in Windber focused on surviving, reuniting their families, and building up their respective ethnic institutions. During World War I they would once again take up the difficult collective struggle to unionize, become part of the American labor movement, gain greater control over their lives, and simultaneously "get Windber Free for Democracy."

Elderly miners and their families interviewed in the 1980s for The Miners of Windber uniformly named the strikes of 1906 and 1922 as the two most significant events in the town's near 100 years of history. Yet these were only two of the most dramatic collective and individual struggles in which working people in Windber engaged over the years, as they sought to unionize, gain greater control over their lives, and secure American constitutional rights and civil liberties in a company town where these elementary features of a democratic society did not exist. Moreover, ongoing struggles for social justice did not end with successful unionization in the 1930s, or with the subsequent closing of the mines and deindustrialization in the 1950s and 1960s, but continue today under new conditions.

What heritage exhibits, and what newspaper articles, accurately remember the aspirations and longterm struggles of Windber-area miners and their families for union? Who has remembered or commemorated the victims of the massacre of 1906? On the 75th anniversary of the landmark strike of 1922-1923, who today remembers the participants, or the conditions which led thousands of Windber-area immigrant and American miners and their families to take part in this particular historic mass struggle? Or the experiences of the area's thousands of working people who encountered the harsh problems of coal-related diseases, poverty, unemployment, mine closings, outmigration, over the years since then?

Additional Reading

- Beik, Mildred Allen. The Miners of Windber: The Struggles of New Immigrants for Unionization, 1890s-1930s. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996. The author is an independent labor historian who is also a Windber native, the daughter and granddaughter of coal miners who worked in Windber mines.

- Beik, Mildred Allen, "The Competition for Ethnic Community Leadership in a Pennsylvania Bituminous Coal Town, 1890s-1930s." In Sozialgeschichte des Bergbaus im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert [Towards a Social History of Mining in the 19th and 20th Centuries], ed. Klaus Tenfelde, 223-241. Munich: C. H. Beck, 1992.

- Beik, Mildred Allen, "The UMWA and New Immigrant Miners in Pennsylvania Bituminous: The Case of Windber." In A Model of Industrial Solidarity? The United Mine Workers of America, 1890-1990, ed. John H. M. Laslett. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996.

- Blankenhorn, Heber, The Strike for Union. New York: H. W. Wilson Company, 1924, reprint, New York: Arno and New York Times, 1969. This is the classic account of the miners' difficult, lengthy strike for union in 1922-1923 in the Windber area and Somerset County, Pennsylvania.

- Brophy, John, A Miner's Life. Edited by John O. P. Hall. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1964. This is the classic autobiographical account of the important labor leader who headed District 2 of the United Mine Workers of America during the strike of 1922-1923, challenged the leadership and business unionism of John L. Lewis in the 1920s, and directed organization of the unorganized under Lewis for the Congress of Industrial Organizations in the 1930s.

- Dougherty, James. The Struggle for an American Way of Life: Coal Miners and Operators in Central Pennsylvania, 1919-1933. Produced, directed, and written by Jim Dougherty. 56 min. Indiana University of Pennsylvania Folklife Documentation Center: Indiana, Pennsylvania. Videocassette.

- Hapgood, Powers. In Non-Union Mines:The Diary of a Coal Digger in Central Pennsylvania August-September, 1921. New York: Bureau of Industrial Research, 1922. This young labor activist's timely descriptions of the stark non-union conditions that prevailed in the Windber-area mines, and the anger and alienation these conditions produced, seemed in retrospect prophetic, given the massive strike of 1922-1923.

- Hirshfield, David, New York City, Committee on Labor Conditions at the Berwind-White Company's Coal Mines in Somerset and Other Counties, Pennsylvania. Statement of Facts and Summary of Committee Appointed by Honorable John F. Hylan, Mayor of the City of New York, to Investigate the Labor Conditions of the Berwind-White Company's Coal Mines in Somerset and Other Counties, Pennsylvania. New York: M.B. Brown, December 1922. This official public document from New York City's investigation into Windber contains photos, testimony, and evidence the committee used to conclude that "the living and working conditions of the miners employed in the Berwind-White Coal Mining Company's mines were worse than the conditions of the slaves prior to the Civil War."

- Williams, Bruce T., and Michael D. Yates. Upward Struggle:A Bicentennial Tribute to Labor in Cambria and Somerset Counties. Johnstown, Pennsylvania: Johnstown Regional Central Labor Council, 1976.