Dr. Irwin M. Marcus, Dr. James P. Dougherty, and Eileen Mountjoy

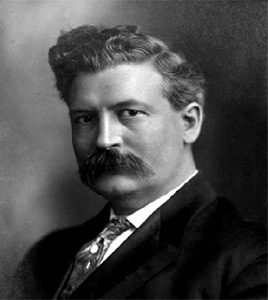

Jonathan Langham, who served as judge of the Court of Common Pleas of Indiana County, Pennsylvania, from 1916 to 1936, shaped political and economic developments locally and mirrored important elements on the national scene. His career on the bench was molded by his conservative Republican politics and his intimate connections with the local political and business elite.

Langham was born August 4, 1861, in Grant Township, Indiana County. He attended public school and graduated from Indiana Normal School in 1882. After teaching school for awhile he read law and was admitted to the bar in 1888. Langham held numerous political positions, including postmaster of Indiana and corporation deputy in the office of the auditor general of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Most impressive, however, was his congressional service. He represented the twenty-seventh District in the 61st, 62d, and 63d sessions of the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1919, he was elected judge of the Court of Common Pleas of Indiana County and won reelection to a second ten-year term in 1925.

During the 1920's, Langham used his judicial power to aid coal companies in their battles against striking miners and the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). His blanket injunction during the Rossiter Coal Strike of 1927-1928 brought him national attention and further polarized the responses to his rulings. Judge Langham's activities had national parallels as the federal judiciary joined with other branches of the government in supporting the reign of big business. Local labor struggles, particularly coal strikes, were parts of national conflicts and the judiciary, usually through the use of injunctions, limited the initiatives of the UMWA leadership in their strike activities. A shift in the balance of power emerged in the early 1930s when the miners gained more public and political support. These developments, personalized in the politic of Franklin D. Roosevelt, spurred the passage of new legislation and the success of organizing drives by the UMWA. On the local level, the retirement of Judge Langham from the bench in 1936 symbolized the end of an era characterized by overwhelming judicial power and the unilateral dominance of big business in labor-management relations.

Between 1880 and 1900 the leading industrial capitalists consolidated their holdings and expanded their wealth and power. In this undertaking, they could usually count on the support of the national political system, whose officeholders identified national progress with economic growth, and the dominance of a relatively unregulated industrial capitalist system. The judicial system played a major role in this arrangement. judge-made law strongly influenced the terms of the public discourse on labor management relations and narrowed the options available to workers and labor leaders who used collective action to ameliorate the condition of the laboring classes. Workers suffered not only from limited income and the threat (or reality) of unemployment and injury, but the master-and-servant law left them in legal subordination, a disadvantage compounded by enforcement of the law by an unsympathetic judiciary. Some workers responded to this situation by turning to unions and strikes as means of collective self-protection. In the 1877 railroad strike, however, they not only faced the wealth of the railroad companies but the power of the state. Railroad executives demanded and received the aid of troops, both the state militia and the U.S. Army. Judges intervened on the side of the railroads by issuing court orders and ordering the arrest of labor leaders for contempt of court. judicial intervention in labor disputes increased in the 1880s and 1890s as judges issued court orders, particularly against boycotts and sympathy strikes.

Developments in Pennsylvania differed somewhat from the national picture. At the national level, railroad strikes, particularly the Gould strikes of 1886 and the Pullman Boycott of 1894, received the primary attention. In Pennsylvania, coal strikes precipitated most of the judicial responses, particularly the 1897 strike and the Westmoreland County strike of 1910-1911. Although Pennsylvania judges issued some injunctions as a result of the 1877 railroad strike, the big change to wider use of injunctions began in 1891 when coal miners successfully lobbied for an anti-conspiracy law mandating jury trials to make it more difficult for companies to get convictions against workers in labor disputes. At this juncture, many company officials turned to the courts for relief The judges responded by issuing more injunctions to protect property rights so that employers could prevent interference with their business by workers who "used force, threats or menace of harm to prevent others from working."

In the World War Oneera, the combination of a sympathetic President Woodrow Wilson and the need for national mobilization brought some gains for workers and the labor movement, but even in this more favorable environment problems persisted for the labor force. Working people benefited from an improvement in the labor market, resulting from a significant reduction in the flow of immigration, and Samuel Gompers and other labor leaders won posts on government boards. The War Labor Board, in particular, offered progressive approaches to industrial disputes, and organized labor grew in membership and strength. New labor leaders also emerged, including John L. Lewis and John Brophy, who played big roles in the United Mine Workers of America in the 1920s. Brophy, president of District 2 of the UMWA from 1916 to 1926, advocated a shorter work week and nationalization of the coal mines. He was a major adversary of judge Langham, particularly in the 1920s. On the other hand, the political system continued to present formidable barriers against effective political action. The Clayton Act of 1914 failed to fulfill the expectations of Samuel Gompers and the lobbyists of the American Federation of Labor who pushed for it. Although section 20, in theory, restricted the use of injunctions, a qualifying phrase that allowed their use in cases of injury to property or property rights facilitated their ongoing use. For example, in the 1917 case of Hitchman Goal and Coke Co. v. Mitchell, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that United Mine Workers' organizing activities infringed on the operators' "property interest" in the nonunion status of their miners and thereby upheld "yellow dog" contracts, which precluded employees from joining unions. The complex nature of federal government involvement in labor-management relations is evident in the Lever Act of 1917, which gave the president authority to control the distribution of food and fuel and established the United State Fuel Administration to help implement this legislation. The miners gained wage increases and membership in the United Mine Workers grew, but when the war ended miners faced inflation and an ongoing prohibition against strikes.

The end of World War One intensified the problems of all workers, including coal miners, as inflation continued to erode their real wages. The Red Scare and the increasingly repressive policy of the executive branch of the federal government added to their woes. The Bolshevik Revolution not only transformed Russia but provided an alternative international politics that many middle Americans and members of the elite viewed as a threat to the American way of life. Antiforeign, anticommunist sentiment produced a wave of repression in the spring and summer of 1919. "Superpatriots" attacked a peaceful May Day demonstration in Cleveland leaving two dead and ten wounded in their wake. Work stoppages added to the turbulence of this tumultuous year, particularly the Seattle general strike, a national steel strike, and a national coal strike. When strikers beseeched Woodrow Wilson for his support, he turned a deaf ear and remained preoccupied with ratification of the Treaty of Versailles. Employers joined with superpatriots in using 100 percent Americanism as a weapon against strikers and as a rallying point to enlist public support.

Coal miners grew restive as the cost of living increased in the aftermath of the armistice, but coal operators refused to consider wage increases and a nationwide coal strike began November 1, 1919. Earlier in the year unorganized coal miners employed by the Potter Coal and Coke Company in Coral, a small town seven miles south of Indiana, struck to obtain recognition of the UMWA as their collective bargaining agent. Indiana County coal operators obtained support from state and county public officials in their battles against the miners and the union. The intervention of judge Langham played a crucial role in the outcome of this strike.

On April 1, 1919, 350 miners struck after the company refused to recognize the UMWA as their bargaining agent. Evictions followed and the conflict intensified. Union officials invoked patriotism and democracy in behalf of the strikers' cause, while company officials lauded their wage rates, criticized the "misleading" statements made by union officials, and asserted that almost all the miners would return to work if they received protection against the Bolsheviks who terrorized the area. Union officials responded to these accusations by drawing parallels between the strike and World War 1, with the Coral strikers presented as upholders of liberty and democracy and company officials in the autocratic posture of Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany.(See photograph below: Coral, Pennsylvaniain 1919-1920 with tent Colony in the background).

The company responded to the union's offensive by seeking judicial remedies in the courtroom of Judge Jonathan Langham. The court heard testimony from company officials and their advocates who alleged that harassment and threats by strikers had reduced the labor force from 250 to 142 and interfered with the conduct of the company's business affairs. In addition to being accused of activities designed to foster the strike, the indictment also charged Peter Ferrara, a District 2 UMWA official, with a specific threat against C.E. Hallar, acting president of the Potter Coal and Coke Company. He threatened to "bring in organizers, establish a camp and torment him for a long time if he did not sign the scale." judge Langham responded to this testimony by issuing a broad injunction on July 3. It forbade strikers from assembling in areas adjacent to the work site or from going to the homes of employees and annoying them.

In late July 1919, Langham penalized strikers who had violated his order against interfering with or intimidating workers who wanted to continue working at the Potter Coal and Coke Company. He charged Tony Bebir, the acknowledged strike leader, and sixteen other defendants, most of whom were foreigners according to a local newspaper article, with contempt of court. Their parades and demonstrations in Coral, and between Coral and surrounding communities, he asserted, had violated his injunction. He, therefore, sentenced them to jail and set no date for their release. The defendants spent from July 22 to July 28 in jail. At this point judge Langham released them from incarceration with stipulations about their future conduct. He prohibited picketing on public highways, at entrances to company property, and at the residences of employees. Although the defendants retained the right to go to the local post office, his order forbade them from congregating a the site in such force as to be intimidating to other patrons. This order had implications for R.E. Mikesell, postmaster of Coral, as well as the striking coal miners. Lindo Brigman, a post office inspector, charged Mikesell with a series of offenses that included allowing the Bolshevik to gather at the post office and sneer at loyal Americans who came to do postal business. Judge Langham's intervention, plus the power and wealth of the company, defeated the determined efforts of the miners and the union. The District 2 Executive Board voted to discontinue the strike at its April 23, 1920, meeting.

Employers registered number victories in the strike wave of 1919, including a triumph in the steel strike. The national coal strike was a partial exception to this patter, with coal miners winning a wage increase but failing to obtain a thirty-hour work week and nationalization of the coal mines. The employers' offensive against workers, strikes, and labor unions continued in the 1920s as many employers began open-shop drives wrapped in the flag, the "American Plan." The era also witnessed business consolidations, increasing productivity, and a shift of labor from goods production to the service sector. While growing profits and increasing production characterized many key sectors of the economy, such as the automobile industry, other sectors, such as coal, suffered from severe problems. Although the bituminous coal industry experienced rapid growth between 1890 and 1920, it was troubled by wastefulness, inefficiency, and excessive competitiveness. The coal industry's search for order proved frustrating and futile as the problem of overproduction became even more intense in the 1920s. Cost-cutting was a key response to intensified pressure on profits as operators mechanized, resisted the passage and implementation of safety legislation and opposed unionization. These measures led to labor turmoil and convinced some operators to seek stabilization through planning. Herbert Hoover, secretary of commerce in the Harding and Collage administrations, sought to stabilize the industry by balancing liberty with order in an approach that blended efficiency with individual action. His initiative led to several conferences and much discussion of the value of industrial associations. However, few concrete improvements resulted from these activities, and the industry remained deeply divided between unionized and non-unionized sectors and labor-management conflicts held the spotlight.

The attitudes and policies of national political leaders provided little solace for discontented wage earners. Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge displayed clear sympathies for big business and saw nationwide strikes as threats to the national interest. Congress, dominated by conservative Republicans, exhibited the same outlook, except for a small corps of progressives led by Senator Robert Wagner, Senator George Norris, and Representative Fiorello La Guardia. The U.S. Supreme Court played a particularly crucial role in labor-management relations, with its decisions restricting the activities of workers and unions, thereby buoying the spirit and power of employers. William Howard Taft, who served as chief justice from 1921 to 1930, set the tone and direction for the Court. His extensive judicial experience began in Ohio in the late 1880s, and his rulings during the 1880s and 1990s usually restricted union activities and supported management rights. He strongly disapproved of the Pullman Boycott of 1894 and condemned Eugene Debs, president of the American Railway Union. His antagonism to unions and labor leaders intensified in the twentieth century as his advocacy of judicial prerogative grew. He criticized the Republican convention of 1908 for mentioning the injunction at all, even though it affirmed the present procedure of the courts. As chief justice he declared the child labor law unconstitutional, upheld the use of injunctions, and condemned strikes and labor leaders.

To counter the policies of employers and their allies, many workers and labor leaders turned to strikes in the early 1920s. The strike wave peaked in 1922, a year that resembled the upheavals of 1919, but which focused on the railroad shopmen's strike and the coal strike. The shopmen's strike began on July 1, 1922, with 400,000 workers struggling to protect the gains won during World War I on wages, trade union recognition, and union work rules. The battle featured on one side railroad executives supported by their allies against the strikers, women's auxiliaries and community supporters. Internal divisions among the shopmen contributed to their loss of the strike, but the intransigence of management and the role of the state proved pivotal. Warren Harding condemned the shopmen and issued antilabor pronouncements, while Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty sent huge contingents of marshals to the strike scene. The injunction issued by judge James H. Wilkerson of the U.S. District Court of Illinois charged the strikers with conspiracy to interrupt interstate commerce, thereby undermining the strike.

In many respects the coal strike paralleled the shopmen's strike, as coal miners sought to defend their right to organize and engage in collective bargaining and to maintain the gains made in the World War I era. The miners also faced intransigent employers, backed by their political allies, and the danger of wage reductions and unemployment resulting from the effects of the industrial depression of 1920-1921. These conditions led John L. Lewis to wage a defensive battle to maintain the wage rate. On April 1, 1922, 600,000 miners nationwide went on strike with unionized miners joined by miners in the nonunion fields (particularly in Somerset County, Pennsylvania.) The miners requested public support in their struggle, offering idealistic and practical arguments in their behalf and declaring that their fight was right. They indicated that additional setbacks would undermine their position as free Americans and erode their purchasing power, which provided the economic undergirding of many communities. In August, John L. Lewis signed an agreement with the owners. It preserved the existing wage scale but abandoned demands for nationalization and the thirty-hour week and deserted the unorganized miners who had responded to the strike can. John Brophy and District 2 continued the struggle in behalf of the unorganized miners until economic burdens forced them to surrender in July 1923.

Crucial elements of the national Strikes had their counterparts in Indiana County. The coal strike of 1919 opened protracted labor-management conflicts that lasted for almost a decade. In the early 1920s authorities combined the use of military force with judicial power, but by the late 1920s the injunction had become the primary tool of repression. The activities and associations of judge Langham, which brought together local political and business leaders, provided a counterpart to the roles of William Howard Taft and Andrew Mellon, secretary of the treasury, at the national level. judge Jonathan Langham had strong ties with the region's political and economic elite. He served as chairman of the Indiana County Republican party and campaigned for State Senator John Fisher in 1926 when this leading Indiana County Republican ran for governor of Pennsylvania. Fisher had served as an attorney for and vice-president of the Clearfield Bituminous Coal Corporation which operated mines in Rossiter, the locale for an infamous injunction issued by judge Langham in 1927. In addition, both men served on the board of trustees of the Indiana State Normal School, Fisher from 1916 to 1927 and Langham from 1917 to 1931. Langham and Fisher corresponded when Fisher served as governor, and Fisher praised Langham's injunction in the Rossiter strike of 1927-1928 and lauded his subsequent testimony before a United States Senate subcommittee. judge Langham also corresponded with Thomas R. Johns, general manager of the Bethlehem Mines Corporation, whose company operated a facility at Heilwood. Langham and Johns exchanged information about political candidates, and Langham requested Johns to support his reelection bid. Johns agreed and declared that he "will with extraordinary pleasure make every effort I am capable of in aiding you to succeed yourself" Johns also corresponded with several superintendents about generating support for Langham. They, in turn, pledged to do everything possible to secure his reelection and promised to turn out the vote at Wehrum and Heilwood. Johns also wrote to G.A. Buck, president of the company, to declare in response to Langham's overwhelming victory in 1925, "We were very interested in helping this candidate." Johns also promoted the campaign of John Fisher whose campaign manager thanked him for circulating Fisher petitions.

Injunctions proliferated in the 1920s, surpassing all previous records. Indiana County participated in this trend as Jonathan Langham issued injunctions in several major labor disputes, including the 1922 and 1927 strikes, At Valier, coal miners struck against the Pansy Coal Company in May 1920. They sought unionization of the mine, a ban on the discharge of miners for union activities, and use of a checkweighman to determine coal weights. The company responded to this initiative by introducing a bill of complaint in the Indiana Court of Common Pleas where judge Jonathan Langham heard the case. Counsel for the plaintiff alleged that many employees wanted to return to work, but the actions and threats of the defendants precluded them from resuming employment. The defendants' campaign of terror, according to counsel, included name calling, visits to the houses of the workers, and carrying clubs. Counsel for the defendants denied that his clients had engaged in interference or coercion, although he affirmed the existence of an organizing campaign by the United Mine Workers of America. Nevertheless, in early August judge Langham issued a permanent injunction against the UMWA. His court order forbade strikers and union officials from assembling at or near the mine and from interfering with employees going to and from the mine by the use of threats, menaces, or demonstrations. The injunction also prohibited the defendants from annoying the plaintiff in the conduct of his business. District 2 officials considered appealing this decision, but they realized that other judges would, most likely, uphold judge Langham's contention that a congregation of protesters engaged in a strike, by its nature, created a menacing environment.

These events provided a prelude for the more dramatic and significant confrontation in 1922. The coal strike of 1922 began on April 1 and was initially centered in Somerset and Cambria counties, but the action soon shifted to Indiana County. By July, 10,000 to 15,000 coal miners held increasingly frequent meetings and marches. Heilwood, a Bethlehem Mines Corporation site, seventeen miles from Indiana, Pennsylvania, became the new focal point of the struggle. In late July Thomas R. Johns, general manager of the Bethlehem Mines Corporation, Heilwood Division, offered Governor William G. Sproul the use of a farm, at no cost to the Commonwealth, if the governor decided to dispatch a company of infantry or a troop of cavalry for strike duty in the Heilwood area. In his letter Johns attributed the reduction in coal production "entirely to the machinations and intimidation of our men by paid agitators." Within a few days of receiving this letter, Governor Sproul dispatched troops of the Pennsylvania National Guard to Heilwood. The National Guard commander prohibited open-air meetings by miners at Heilwood. Miners and union leaders condemned this decision and the actions of National Guard troops as violations of the Constitution and a denial of the rights of free citizens, but troops remained at Heilwood until early September.

The presence of the National Guard received most of the public attention, but the judicial system played an important role in the strike. In late July and early August the Indiana County Court of Common Pleas held a hearing to respond to a request from the Bethlehem Mines Corporation for an injunction. In the aftermath of a mass meeting by miners at the Heilwood tent colony on July 27, witnesses for the company informed the court that the mines could not be operated without guards, although only one witness alleged that actual intimidation had occurred. They testified that residents feared bodily harm and the danger posed by houses being blown up. Some witnesses also condemned the content of both union circulars and the Penn Central News, a publication of District 2. judge Langham responded by issuing a preliminary injunction. In this document Langham restrained striking miners and union officials from interfering with the operation of the Bethlehem Mines Corporation mines in the Heilwood area and prevented them from undertaking any activity that hindered miners from going to work. Although coal operators and District 2 Officials eventually signed an agreement that retained the old wage scale, the injunction continued in effect into 1928.

The judicial situation in Indiana County in the 1920s had many parallels on the national judicial scene. The courts placed restrictions on the rights of unions to conduct their affairs. The term "property," which embraced intangible property, became the latticework up which the labor injunction climbed. The extraordinary remedy of injunction became the ordinary legal remedy, almost the sole remedy. The injunction placed the most powerful resources of the law on one side in bitter social struggles. Controversies in the coal fields became a critical arena for the use of injunctions, and their use contributed to the growing strength of businesses and the increasing weakness of labor unions. A majority on the U.S. Supreme Court took the lead, and most federal judges shared their prejudices against organized labor. These developments can be seen in a series of coal strike cases in which the United Mine Workers became the leading defendant in suits brought under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. In the Coronado case, the United States Supreme Court decided that the UMWA could be sued. The Borderland case restricted the sphere of permissible activity by the union, as did the Red Jacket case in which the federal courts upheld the coal company's assertion that the United Mine Workers had engaged in a conspiracy to restrain interstate commerce in nonunion fields by interfering with the operation of the plaintiffs' mines in West Virginia.

The Rossiter strike of 1927-1928 brought both the sweeping injunctions of judge Langham and the situation of Indiana County coal miners and their families to national attention. This confrontation had its roots in the deteriorating situation in the Pennsylvania coal fields and the increasing antagonism between the operators and the miners. The general troubles of the coal industry had grown by the mid-1920s, and the coal operators sought relief from several quarters. They requested aid from the federal government, including changes in transportation rates that would make coal produced in the north more competitive with southern coal. However, the coal companies focused most of their attention on labor costs and sought "concessions" from the miners and the union. By 1927, almost all the big mining operations in Indiana County had abrogated the Jacksonville Agreement of 1924, which resulted from the wage awards following the 1919 strike and provided for a daily wage of $7.50. The Clearfield Bituminous Coal Corporation was the major exception to this trend. It maintained the Jacksonville Agreement until 1927, but at this juncture its officials contended that the company could not remain competitive at such a high wage rate and, therefore, demanded an "adjustment" from the miners and the union.

The Clearfield Bituminous Coal Corporation, especially its Rossiter facility, became the focal point of the coal strike of 1927 in Indiana County. The strike began on July 1 when 800 miners at the Rossiter site joined other miners in western Pennsylvania in a major strike. The miners adopted resolutions requesting aid, and they engaged in direct action highlighted by marches to other mines in the vicinity, where they sought to convince those miners to stop working. The level of conflict intensified as authorities stationed state troopers and sheriffs deputies at Rossiter and many miners suffered from evictions. judge Langham entered the fray in November by issuing a sweeping preliminary injunction that blocked virtually all the activities of Rossiter strikers and UMWA officials. His injunction forbade picketing and marching or gathering for meetings or rallies. It prohibited the disbursement of union funds as relief for striking miners. The order also forbade newspaper advertisements and other means of communication from being used to aid the cause of the strikers and convincing miners to desert work. However, most of the furor arose from Judge Langham's prohibition against singing hymns and holding church services on lots owned by the Magyar Presbyterian Church situated directly opposite the mouth of the mine.

This sweeping injunction and the activities of the coal and iron police helped to give the company the upper hand, but the strikers and the union tried to maintain their morale and to sustain the struggle by holding frequent church services and conducting an outreach campaign. Union miners continued to march to nonunion camps to solicit the support of those miners. The United Mine Workers hosted rallies, tried to find housing for evicted miners, and solicited help from the public. The effort to get public support bore the most fruit in the Punxsutawney area. The Central Labor Council of Punxsutawney solicited contributions of money, food, and clothing in the business district of the town. Many merchants responded to these requests with donations of clothing, shoes, and money. Monetary contributions also came from individual donors and such organizations as the Knights of Phythias, the Catholic Daughters of America, and the Fraternal Order of Eagles.

The strikers and their supporters also received a boost to their cause when a subcommittee of the Interstate Commerce Committee of the United States Senate arrived in Indiana County in late February 1928. The presence of committee members and a press entourage placed the plight of the coal miners in the national spotlight. The senators saw the issues in the strike as transcending labor-management relations and involving crucial questions of civil liberties. This perspective was reflected in their questioning of witnesses who appeared before the subcommittee. judge Jonathan Langham began his testimony by explaining the execution of the injunction process in the Rossiter case. He described how he issued a restraining order supported by affidavits, although the court heard no testimony at the time nor had any testimony been offered since that time---a procedure that had no precedent in his judicial career. At this point the testimony shifted from procedural to substantive issues. Langham. told Senator Robert Wagner that a striker had no right to persuade or restrain someone who wanted to go to work. Their dialogue continued as Senator Wagner asked whether the Langham injunction violated the strikers' freedom of speech. Senator Burton Wheeler joined the exchange with particular emphasis on the issue of hymn singing. While Senator Wheeler viewed the prohibition of hymn singing as "getting into a pretty dangerous thing," judge Langham described the hymns as "hostile songs." By the end of Langham's testimony, a clear contrast in viewpoints on crucial civil liberties issues had emerged between the jurist and the senators.

The issue raised by judge Langham's opinions and activities aroused the attention of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) which dispatched a staff member to the scene. William Nunn, a professor of economics at the University of Pittsburgh, visited Indiana County and provided the ACLU with several research reports on the situation. He presented highlights of developments in the strike, described violations of the rights of the strikers, and offered "very confidential" recommendations. In addition to mentioning the Langham injunction, he noted that state troopers broke up a church meeting, and police had dispersed a mass meeting and driven church members down the street. In his recommendations, Professor Nunn requested that the ACLU respond to the need of the strikers for legal aid, including assistance to Reverend A.J. Phillips if he held meetings in violation of the Langham injunction. In addition, he recommended that the ACLU confer with Bruce Sciotto, counsel for the United Mine Workers, if it wanted to pursue impeachment proceedings against judge Langham. Professor Nunn asserted that there was much material to substantiate a claim of his unfitness to be a judge. In particular, he emphasized Langham's ownership of stock in coal companies, the use of coal company funds in his reelection campaign, and his indiscreet remarks about the strike. An experienced investigator should be recruited to operate secretly in collaboration with Sciotto and officials of the United Mine Workers, if the organization desired to pursue impeachment proceedings. Professor Nunn declared that this type of investigation would provide grounds for impeachment and shock the legal profession.

Press coverage and editorial comment aroused public attention concerning the Rossiter strike and the Langham injunction. It also reinforced the effect of the presence of the sub-commitee of the Senate Committee on Interstate Commerce. The Punxsutawney Spirit and the Indiana Evening Gazette provided the most detailed and extended coverage of the strike. Pittsburgh newspapers dispatched reporters to cover the hearing and events in Rossiter. Lowell F. Limpus who reported on the committee proceeding for the New York Daily News also testified before the committee. His photographs graphically told the story of poverty witnessed by the senators. The New York Times provided coverage of the hearing on February 28 and 29, calling the injunction against hymn singing "one of the most drastic injunctions . . . in the history of labor disputes in this country." In addition to articles about the strike, the United Mine Workers Journal printed a letter by A.J. Phillips lamenting the poor physical condition of the miners and the decline in outside donations and requesting the passage of remedial congressional legislation. The injunction and the call of the Rossiter miners for a general coal strike caught the attention of the Daily Worker, which described the Langham injunction as "the most drastic injunction ever granted in this state."

Community support and the favorable publicity generated by the congressional investigation boosted the morale of Rossiter strikers. However, their adversaries had all the advantages in this protracted labor war of attrition. In addition to the force of Langham's injunction, they had more wealth, more political power, and more support from the local press. This combination of elements spelled defeat for the miners and the union. By the end of August 1928 virtually every mine in District 2 was operating on a nonunion basis. Most of the miners were paid the Philadelphia rate of $6.00 a day, rather than the Jacksonville scale of $7.50 a day, which the Rossiter miners and other District 2 miners had sought to protect in their 1927-1928 strike.

The labor injunction was the principal weapon used by Judge Langham in responding to strikes by coal miners and the United Mine Workers of America. However, he also became involved in labor disputes in other ways. In the midst of the 1919 coal strike he denied the naturalization applications of striking coal miners because he viewed their refusal to return to work as inappropriate conduct for a potential citizen. He also became involved in incidents connected with the coal strike of 1927-1928 outside the Rossiter area. Minor infractions of the law by coal miners, such as disorderly conduct and alleged violations of the sheriffs proclamation, led judge Langham to assess a bond of $2,000, while a deputy sheriff accused of shooting and seriously wounding a person without provocation obtained his release on payment of bail in the same amount. The favoritism and partiality of the court can be seen in another case in which judge Langham released a deputy sheriff charged with murder on a bond of $5,000.

By 1928, the UMWA retained little strength in District 2. County coal miners faced reduced wages and the threat of unemployment, as well as intransigent coal operators. In Rossiter, for example, A.J. Musser, vice-president of the Clearfield Bituminous Coal Corporation, sent a letter to his employees on February 28, 1928, in which he reiterated the nonunion policy of the company. Other coal companies followed a similar policy. Some Rossiter residents left town looking for work, while the miners who remained in town divided between those who returned to work and those who refused to do so. Conditions worsened in the early thirties. The number of employed miners plummeted and workers had to perform much unpaid labor and patronize the company store. When desperate miners sought the aid of their union leaders, neither James Mark, president of District 2, nor John L. Lewis could provide assistance.

Under these conditions some Indiana County coal miners turned to collective action in the summer of 1931 by affiliating with the National Miners Union (NMU) or the UMWA and engaging in strikes. The Sagamore strike initiated by the NMU, a Communist-dominated labor organization, began the strike wave and provided a catalyst for other strikes. The miners demanded union recognition, a checkweighman, and changes in the policy on "dead work," (unpaid labor). Deputies were dispatched to the strike scene to monitor and restrain the actions of the miners. Once the Sagamore mines were closed, miners from Sagamore used parades and marches to convince miners at other sites to join the strike. At this point John Ghizzoni, a member of the National Executive Board of the UMWA, began to play a larger role in the strike by delivering speeches and calling for peaceful picketing. As the strike spread into Indiana County, coal miners participated in parades and struck operations of the Rochester and Pittsburgh Coal Company, one of the largest coal companies in the county. The miners at the McIntyre mines played a key role in the Indiana County strike wave that strengthened the UMWA.

The Rochester and Pittsburgh Coal Company responded to the strikes and the unionization drive by turning to judge Langham. and the Court of Common Pleas of Indiana County for relief by injunction against the miners and the union. Langham declared that the defendants "engaged in an organized conspiracy unlawfully to force the plaintiffs to submit to the dictation of the aforesaid defendants or close their mines." He pinpointed specific actions for condemnation, including marching, picketing, and jeering, and criticized specific demonstrations, particularly an action at McIntyre on July 16. These activities, judge Langham contended, would prevent the plaintiffs from fulfilling profitable contracts for the sale of coal and result in irreparable damage and the ruination of their business. On this basis, judge Langham enjoined the defendants from engaging in any scheme to hinder employees from working by marching, picketing, and using insulting epithets. The defendants were further enjoined from any action that would impede the plaintiffs in the operation of their coal mines. In a special twist to the case, judge Langham delivered a stern lecture to the defendants, especially John Ghizzoni, in which he criticized them for their actions and condescendingly characterized them as "good honest laboring men," and admonished them to conduct themselves as "orderly citizens." He continued his display of paternalism by deferring their sentences for contempt of court if they agreed to pay court costs and promised by holding up their hands to obey his injunctions.

The strike had repercussions beyond Indiana County and adjacent counties. Governor Gifford Pinchot sent a telegram of protest to B.M. Clark, president of the Rochester and Pittsburgh Coal Company, condemning the proposed evictions of miners and their families because the miners had joined the UMWA and wanted a checkweighman. Pinchot characterized the threatened evictions as "barbarous" because they would not only deprive the families of their homes, but would also cost them their gardens which supplied essential food. Clark responded by declaring that Governor Pinchot was misinformed. He asserted his employees had no complaints, received high wages, and did not want "invaders" from the United Mine Workers in their midst. He concluded his response by accusing UMWA officers of a lack of decency and humanity and exonerating company officials of the charge.

In the 1930s, workers and labor leaders finally achieved a national political system more favorable to their interests. The shift began in the late 1920s when attitudes of the public and politicians became more critical of judicial prerogative, especially the extensive use of injunctions. Senator George Norris of Nebraska, who played a crucial role in the legislative process, witnessed the intolerable conditions of Pennsylvania coal miners and called for nationalization of the coal mines and restrictions on the use of injunctions. Representative Fiorello La Guardia of New York, who would cosponsor the Norris-La Guardia Act of 1932, also saw the plight of Pennsylvania coal miners and their families. He too sought nationalization of the mines and restrictions on the use of injunctions as necessary remedial measures. After several abortive attempts to pass anti-injunction legislation the cosponsors achieved their goal. The Norris-La Guardia Act of 1932 led to the extinction of the yellow-dog contract and made the use of injunctions less frequent.

In 1932, the national political landscape changed with the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt as president. Roosevelt undertook a number of immediate initiatives highlighted by the National Industrial Recovery Act establishing codes of fair competition for key industries, including the coal industry, and affirming in section 7A of the bill the right of workers to engage in collective bargaining. This legislation combined with the ferment among workers and dynamic labor leadership to reinvigorate the labor movement----especially the UMWA.

A second phase in the growth cycle of the labor movement began in 1935 when John L. Lewis and his associates formed the Committee of Industrial Organizations and Robert Wagner realized his dream with the passage of the National Labor Relations Act. Wagner, who had been a champion of workers and labor unions for a quarter-of-a-century, had an intimate knowledge of the plight of New York workers. He learned of the coal miners' plight when he visited Indiana County and interrogated judge Langham and other witnesses during the Senate subcommittee hearing in 1928. The Wagner Act accorded employees the right to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, restricted employers through a list of unfair practices, and created a National Labor Relations Board to administer the legislation. Contemporary opinion of the legislation was divided; the press and the business community opposed it and organized labor favored it.

Scholars also diverge in their interpretation of the impact of the Wagner Act. Irving Bernstein and Karen Orren point to a "revolution in labor law" in which the power of Congress expanded while judicial prerogative shrank. Orren describes the Supreme Court decision in NLRB v. Jones and Laughlin Steel, upholding the National Labor Relations Act, as signaling the "official repudiation of common-law governance in labor relations." It marked the final dismantling of the order of master and servant and the shift to the modem liberal state. Power previously centered in the judiciary shifted to Congress. Alan Dawley also appreciates the importance of the Wagner Act for enhancing the position of labor as a collective entity deserving state protection, but it failed to make labor the peer of business. In other words, New Deal labor policy raised the status of industrial workers even as it affirmed their subordinate position under the dominance of the modem corporation. James Atelson offers a less sanguine assessment of the effects of the Wagner Act on the employment relationship. He declares that while the National Labor Relations Act "created a substantial zone of protection for employees wishing to join and participate in a union," it left undefined zones of employer prerogatives to be defined by the courts. Although Atelson appreciates the accomplishments of collective bargaining in limiting the exercise of managerial power, the institution does not seem to have altered basic legal assumptions about the workers' place in the employment relationship. Christopher Tomlins also notes the limitations of the Wagner Act from the vantage point of the workers. The acceptance of collective bargaining derives from its ability to produce "industrial stability and labor peace" and is judged by its value in achieving this goal. Tomlins concludes that labor leaders and workers should realize "a counterfeit liberty is the most that American workers and their organizations have been able to gain through the state." Instead, they must look to themselves to achieve their goals.

Developments at the state level had many parallels with the national picture. State-sponsored anti-injunction legislation even preceded national legislation. In 1931, the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed a law that limited the power of courts of equity to issue injunctions in labor disputes. The Pinchot administration sought the passage of other measures to benefit workers, but the governor's efforts were stymied by 'a recalcitrant state Senate. Nevertheless, his initiative helped to set the stage for George H. Earle III who became governor after winning the election of 1934. The Democrats not only won the governor's chair, but Joseph Guffey won a seat in the U.S. Senate where be cosponsored several pieces of coal legislation designed to stabilize the industry. The Earle administration included Thomas Kennedy, secretary-treasurer of the United Mine Workers, as lieutenant governor and Charles Margiotti, an attorney for the United Mine Workers, as attorney general. The Earle administration obtained legislation that outlawed the coal and iron police, established a Labor Relations Board, and further restricted the use of injunctions. Thus, Pennsylvania Democrats could point with pride to their "Little New Deal.

Events in Indiana County were influenced by, and drew inspiration from, these national and state developments. On May 14, 1933, Philip Murray, vice-president of the UMWA, spoke at a rally in Clymer, a small town ten miles north of Indiana, before a crowd of 4,000. After the meeting 700 miners joined the UMWA. Organizers followed with rallies and recruitment drives in other Indiana County towns. The United Mine Workers Journal of June 1, 1933, reported that two locals in Rossiter had reorganized, and the town was almost 100 percent unionized. These organizing breakthroughs gave the 1933 Labor Day festivities a special character. The event featured a parade, a dance, and a diverse roster of speakers that included judge Jonathan Langham and John Ghizzoni. judge Langham, who delivered the first of the four-minute speeches, expressed his appreciation of Labor Day and called for renewed support of the National Industrial Recovery Act. John Ghizzoni, the event's major speaker, stated that mine workers were pleased to participate in Roosevelt's program for renewed prosperity in the United States. The rise of the United Mine Workers had implications for Indiana County politics. In 1934, District 2 UMWA created a Labor Non-Partisan League as a political vehicle. Its leaders linked the fortunes of UMWA and the Democratic party, placing particular emphasis on Thomas Kennedy's race for lieutenant governor. The UMWA's political involvement helped the Democrats capture over 46 percent of the county vote, a significant improvement over the party's performance in the 1920s and early 1930s. Two events in 1936 symbolized the shifting power relations in Indiana County. John L. Lewis spoke at the Indiana Fair Grounds on October 24, 1936, before a large crowd of ten to twenty thousand. Lewis declared "Americans today are no longer contented with the way labor has been exploited by financial and industrial leaders who have controlled the political situation." He also praised the UMWA as "the shock troops to restore industrial democracy." The rally was chaired by James Mark, president of District 2, and the platform committee included Thomas Kennedy and Charles Margiotti. In 1936, Langham retired from the bench after twenty years of service as judge of the Court of Common Pleas of Indiana County.

The judicial career of judge Jonathan Langham, especially between 1919 and 1931, coincided with an era of labor strife, big business dominance, and judicial prerogative. Langham's injunctions buttressed the interests of an elite that used the political system for its own purposes. Conservative Republicanism, a Langham credo, foreclosed meaningful political participation by many groups and excluded their agendas from the mainstream political process during the 1920s. Labor unrest, the coming of the New Deal, and growing influence of the UMWA shifted political power in Indiana County in the 1930s. The meaning of Langham's involvement in the 1933 Labor Day activities remains unclear, however; was it a new direction or an aberrational act? The labor legislation of the 1930s, especially the Norris-La Guardia Act and the National Labor Relations Act, increased the power of unions and provided some protection for workers, but scholars still debate the extent and duration of these changes. Although important political and economic changes occurred in the 1930s, the issue of whether judge Langham's retirement ended an era of big business domination and judicial prerogative remains controversial. Never a peer of corporate power, the labor movement today is relatively small and weak, operates from a defensive posture, and is in danger of continuing decline. Meanwhile big business, with its international horizons, commands great wealth and power. Finally, the injunction has remained a judicial weapon available to business in strike situations, although it has been used less frequently in the post-Langham era. Coal miners and the UMWA, who bore the brunt of Langham's injunctions, have faced judicial wrath and harsh penalties in the post World War 11 era, particularly in the coal strike of 1946 and the Pittston strike of 1988-1989. In both cases judges condemned union activities and imposed huge fines on unions for violating their injunctions.