This article originally appeared in the Indiana Gazette, July 8, 1980 Reprinted with permission.

Eileen Mountjoy

This summer's Diamond Jubilee at Clymer marks seventy-five years of hard work, struggle, and daily joy of living for three generations of Americans. Throughout the history of the town, fires, floods, spectacular ice jams, and Indiana County's worst mine disaster were interwoven with civic pride to achieve a community worthy of the ambitions of its first settlers.

Celebrations like this year's are an established part of Clymer's past. One of the first in a long tradition of "gala occasions" began on the morning of July 20, 1915, with a Homecoming and Fireman's Carnival. On the following day, in observation of the town's anniversary, a letter, from the Honorable John S. Fisher, was read aloud to "a large crowd."

In the letter, Fisher, who was unable to attend, recalled "the events and some of the persons who were identified with the founding of Clymer. "It is," wrote Fisher, "known to all of us that the town had its inception in the purchase by large operating companies of the rich coal deposits in what is known as the Dixonville Field. In these purchases I had an active part for the interests directly connected with the New York Central Railroad. At first, the thought was to build what is commonly known in the area as a "coal town." It fell to the lot of the writer to prevail upon those who controlled the situation to undertake the founding of an open town. This determination was reached in early March, l905. At a conference, the present location of Clymer was decided upon. That night I returned to Indiana and sent Mr. P.M. Sutton to take an option on that portion of the property which was owned by Mrs. Nancy O'Neil, wife of E. O'Neil, Esq. This and other land was transferred to the Land Company which was subsequently organized.

"The Land Company, and the incorporators were William D. Kelley, Rembrandt Peale, and R. A. Shillingford. Throughout the summer months the site was cleared, lots laid out, streets and alleys improved, and, on October 11 and 12, 1905, the company advertised the public sale of lots. As is the usual case with christenings, the naming of the new town received a good deal of consideration, and, it was the good fortune of the writer to suggest the name which was finally adopted, viz., Clymerto honor one of the Revolutionary Patriarchs."

As recorded by Fisher, the morning of the sale dawned wet and dreary, and when the auctioneer climbed upon his block, "two or three hundred serious-looking, if bedraggled, men" stood assembled. A walk through the chilly drizzle also awaited them, as "they came on a special passenger train which brought them only as far as the track had been completed--- to Mitchell's Mills." Later events proved that the men were indeed "serious," for on the afternoon of the 11th and 12th, the auctioneer knocked down 103 lots at the average price of a little more than $306 per lot.

The buyers at the sale were evidently men of faith and determination, for much of the site still presented a " scrubby growth of timber and rocks which were populated with copperheads and rattlesnakes. The residue was made up of worn-out and practically deserted farmland. The location had always been regarded as a secluded section of Indiana County.

This state of affairs was only temporary, for less than a year later, "thanks to the splendid business ability and fine vision of William D. Kelley, of Philadelphia, Hon. W. D. Bigler, and R. A. Shillingford, of Clearfield, former Senator Peale of Lock Haven, and Rembrandt Peale of St. Benedict, the building of the town began.

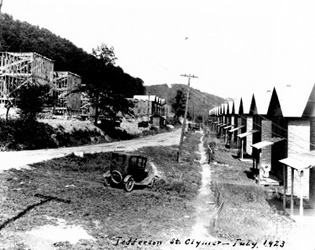

"In 1906, " recalled Fisher, "almost by magic there sprung up dwellings, stores, stations, and all kinds of buildings essential to the life of an active community. So rapid was the growth that when 1908 arrived and the town was only a little more than two years old, steps were taken to have it incorporated into a borough. The borough soon outgrew its original limits by an extensive addition. The growth of the population has been correspondingly rapid. When the census of 1910 was taken, Clymer was the third largest town in size within Indiana County, being only surpassed by Indiana and Blairsville."

After reading Fisher's letter of congratulations, Clymer's 1915 celebration continues with a concert, a baseball game with Rossiter, (Clymer won,) and the placing of the cornerstone of the new municipal building. General Harry White, one of Indiana County's "prominent residents," gave an address, followed by a parade of businessmen and merchants. On July 22, the week-long festivities carried on with Fireman's Day, which featured races and water battles between local and visiting firemen. July 23rd, the Indiana Progress announced, was "Miners' Day," with parades, addresses by W. B. Wilson, then U. S. Secretary of Labor, and first-aid and mine rescue demonstrations. On Saturday, July 24, there were "band concerts, baseball games, and dancing in the park each evening."

By the time of Clymer's "Gala Week" in 1915, the town had already experienced a remarkable amount of both joy and sorrow. The year of the town's approval as a borough, 1908, ended on a sensational note when local papers reported a "riot" at the dedication of "the new Slavish church at Starford," which resulted in the stabbing of eight men. "Some of the men," the paper reported, "were already intoxicated when they boarded the New York Central train for Clymer and a free-for-all fight began on the train." When the passengers disembarked from the coach, the trouble evidently broke out with renewed fury on the street. Eight of the men were so seriously injured that Dr. H. Ney Prothero, Clymer's first doctor, was called in. One of the rioters "was stabbed five times, and is in serious condition," the newspapers announced. "He has three gashes on his head and one of his ears is almost cut off."

Apparently, no deaths resulted from the fracas, and 1909 began with great enthusiasm . Early in the year, state health officials completed their census of Clymer, and reported that "the new borough has 1,662 inhabitants in that bustling little town. There are 412 buildings, which include a number of handsome dwellings, several stores, and an opera house."

In July, newspapers reported that "Clymer, in order to make an up-to-date community, has organized a water company. Numerous springs are to be found within a short radius of the town, with pure water. Summer holidays that year were highlighted by a live play, "Strongheart," presented at the Clymer Opera House by the Normal School Erodelphinians.

By the beginning of December, 1909, Clymer residents were thinking about Christmas, and most of the town's thirty-two shops were decorated with wreaths and holly. Suddenly, Yuletide plans were forgotten, when, just before midnight on December 19, a driver from the Neeley livery stable, on his way to meet a late-night trolley, noticed flames shooting from the rear of the Opera House. About that same time, the trolley arrived, and the motorman sounded his whistle to "summon the populace." Volunteer firemen, buttoning their jackets as they ran, arrived on the scene in minutes. Although fire hydrants stood in strategic locations around the streets, there was no hose, so firemen quickly established a bucket brigade. Valiantly, they battled the blaze until the arrival of the Indiana Hose Company in a special trolley, a little over half an hour later. Volunteers quickly attached the hose to a nearby hydrant, and spouting water doused the flames.

By dawn, onlookers stood silently surveying the devastation. The fire, which ignited in one of the Opera House dressing rooms, had destroyed four stores, two apartments, and five houses before being brought under control. W. F. Neeley's livery stable, located under the Opera House, suffered heavy damage, with a number of buggies, a horse, and two pigs lost in the blaze. The Neeley Hotel, with Dr. H. Ney Prothero's residence adjoining, caught fire, but water was thrown on the roof, saving the buildings from total ruin. After leveling the Opera House and livery, the flames spread to Spasko's foreign banking exchange next door. "Nothing but a smoldering pile of timbers remains to mark the site once occupied by these structures." Sadly, many of the persons who incurred losses had little or no insurance on their property. Losses exceeded $20,000, quite a sum for that day.

Damages were not all calculated in losses to property, as The Indiana Evening Gazette reported the next day. "Several of the firemen are laid up with bronchitis (probably smoke inhalation.) The sick included John Collins, who fell off Dr. Prothero's house while working with the bucket brigade, and Councilman Earl Reed, who had a prominent part in fighting the flames.

In the face of the tragedy, the citizens of Clymer responded with remarkable vigor. Three days later, with the charred wreckage of a half a block of buildings still steaming in the crisp winter air, local newspaper headlines proclaimed: "Clymer Ready for Next Fire! One Thousand Feet of Hose and Two Carts Ordered." Under the caption, the article continued: "With firefight apparatus practically on the way and an abundant supply of water in the town, Clymer folks are feeling easier and assume a cheerful air when anyone mentions fire losses."

In retrospect, even the loss of the Opera House seemed a little less catastrophic as "it turns out the Opera House was condemned some months ago and residents are congratulating themselves that when the fire broke out, it was unoccupied. There were no fire escapes and a building inspector had never been inside."

Although the kerosene-lit splendor of Clymer's Opera House was never recreated, entertainment was soon available in the Knights of Pythias Theatre, which provided "moving pictures." The State Theatre, "one of the most beautiful playhouses around, with blue leather seats and a new piano," opened in November, 1923. Halloween parades, Fourth of July celebrations, lodges, and the activities of various service groups also helped round out Clymer's recreational facilities.

By 1915, the disastrous fire was largely forgotten, and Clymer residents had many reasons to celebrate. At that time, Clymer was the largest town in Cherryhill Township, with a population of 2,000 "made up largely of Americans." Two hotels, the Neeley and the "Clymer House," and several boarding houses served those without a permanent home. Thirty-two stores and shops were available for the purchase of everything from groceries to custom-made suits. Two schools and four churches completed the picture.

New train transportation to and from Clymer was supplemented by the trolley tracks which arrived in April, 1908. At that time, cars ran to the Ninth Street Bridge and business was "quite brisk." The fare from Indiana to the town limits of Clymer was originally 25 cents, but when the trolley entered the new borough, five cents was added to the toll. As Clymer "is only a little over ten miles away," several persons complained to the operators that the cost was "excessive." A year later, trolley schedules were adapted to oblige travelers wishing to make connections with all "steam railroads" at either end of the line

The streetcar line, while providing a great convenience for Clymer's citizens, was the scene of at least two very dramatic incidents before the coming of the automobile brought about its decline and eventual abandonment. In August, 1915, A. R. Wyncoop, of Clymer, was fatally injured when a New York Central train collided with a Street Railways car at the Sample Run Crossing. Eleven passengers in the car were thrown forward by the impact of the collision, but all escaped serious injury. The streetcar, however, was almost totally demolished. Wyncoop was not a passenger in the trolley, but was standing in a small shelter nearby, waiting to board the car. The streetcar, when struck by the train, was hurled completely around, crashed into the little station with full force, and fatally injured Wyncoop.

Another trolley car, this one in 1924, was featured in Indiana County history when bandits waylaid and robbed the Russell Coal Company payroll on its twice-monthly transportation to Clymer. Inside the car, Alexander Caldwell, company paymaster and Tony Askey, Clymer chief of police, guarded the cash, which totaled $23,750 in bills and silver. On the afternoon of June 17, the car reached the siding where it usually waited for the Indiana-bound car to pass. As it had done on countless similar occasions, the Indiana trolley passed the stopped Clymer-bound car and continued on its appointed rounds. Suddenly, an occupant of the stopped trolley jumped to his feet and fired a shot through the roof of the car. The rest of the robbers, planted in strategic seats, brandished pistols and told everyone on board to put up his hands.

Pointing their guns directly at Caldwell and Askey, the bandits tore open the sacks containing the money, secured the cash, and ordered all the passengers and the motorman outside.

This accomplished, the felons promised to shoot anyone who moved. With the trolley empty, four of the felons climbed back on board, still waving their guns in the direction of the passengers, while a fifth man took the motorman's place at the controls. In spite of his probable inexperience, the substitute operator propelled the trolley down the track at breakneck speed , until he reached a site, marked by a white cloth tied to a tree branch, where a new Studebaker waited.

Transference of robbers and cash from trolley to automobile was quickly made, and the men and the money disappeared from Indiana County forever.

The $23,750 robbery of the coal company payroll, on its way to Clymer, indicates that, from the beginning, the production of coal formed the foundation of the community. Although the rich coal deposits beneath Cherryhill and Green Townships had been surveyed before the turn of the century, the first large-scale mining in the area was undertaken by the Clearfield Bituminous Coal Corporation. The C.B.C. was formed in 1886 by a reorganization of the old Clearfield Bituminous Coal Company. In 1895, the C.B.C. acquired 2,000 acres of coal lands in Cambria County. Its West Branch Mine opened there that same year. By 1898, the C.B.C.'s commercial sales of coal were halted and its mines became producers of "captive" coal, with all of its product reserved for fuel for the New York Central Railroad.

In 1900 another block of 15,000 acres was purchased in central Indiana County, and in 1905, mines were opened at Clymer and Barr Slope. In Dixonville, Clymer No. 1, known as Sample Run, and Clymer No. 2, were both just outside the town, but as recalled by John S. Fisher in his tenth anniversary letter, Clymer itself formed "the Center of the operation."

The Russell Coal Company, part of the Peale family interests, and the Pioneer Coal Company, with its Rodkey and McKean mines, were also manned by Clymer men, many of whom lived along the north end of town. Coal mined at Clymer was shipped at an average of 2,500 tons a day in 1915, over the tracks of the New York Central Railroad.

Coal operations at Clymer, under the leadership of C.B.C. presidents W.D. Kelley, W.C. Brown, A.H. Smith, F.E. Herriman, and W.F. Place, kept pace with the railroad's fuel requirements throughout the era of the steam locomotive. At first, simple mule haulage brought the coal from the face of the mine to the outside, but by 1909 engines and rope haulage replaced four-footed transportation. In the early twenties, the company built a central power plant, equipped with sufficient boiler capacity to supply all of C.B.C.'s Indiana County mines with electricity. By the end of World War Two, all of Clymer's mines were equipped with the latest in ventilation, cutting, and loading machinery with less than six per cent of the company's output produced by pick mining. Included were 71 locomotives, 19 scraper-loaders, two Joy mobile loaders, and a belt conveyor system.

A large machine shop was located at Clymer to service the company's heavy equipment. At the shop, workers performed various types of repair work, winding of armatures, welding, and general machine shop work. A supply house, containing a stock of repair parts and mine supplies, reduced time lost for repairs and replacements underground.

Clymer's miners have had a long history of union organization; one "gala day" in 1911 celebrated the visit of John Mitchell, Patrick Gilday, John White, and several other officials and organizers of the United Mine Workers of America. Clymer's U.M.W. Local 1489 arranged, for the visit, an agenda of ball games, races, and parades, and made Mitchell's appearance "one of the greatest holidays this town has ever seen."

By the mid-1920s, Clymer miners were adjusting to the economic slump preceding the depression; often the mines worked only half-time. In the summer of 1926, life at first seemed ordinary; the Fourth of July had come and gone, but long, pleasant evenings still remained for baseball games and family reunions. The, on the afternoon of August 26, the sleepiness of the waning summer was shattered by the reverberations of an explosion deep inside the Sample Run mine. Two days later, forty-one dead miners lay in an emergency morgue in the Clymer machine shop; three more remained underground for several days. The men, women, and children of Clymer, and all of Indiana County with them, were stunned with grief and disbelief. Fifty-six years later, memories of the tragedy still linger.

After the Sample Run disaster, residents of Clymer slowly picked up the pieces of their everyday life; in time, the mining industry once again went about the business of mining and shipping coal. Church socials and new movies shared their place as topics of conversation with the waters of Two-Lick Creek, which annually threatened to overflow their banks. In 1924 and again in 1936, Sherman Street residents found their homes surrounded by water; over a period of years, floods claimed several victims. In 1919 and again in 1928, heavy spring rains caused ice jams of monumental proportions.

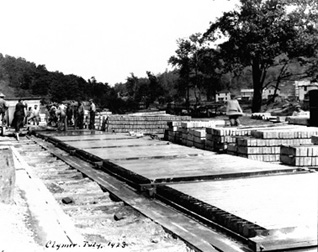

During Clymer's "boom years," a second industry followed closely behind coal production as the economic backbone of the town. From early surveys, investors knew that vein of fire clay lay beneath the seams of coal underneath Cheryhill Township. Parallel to the development of the coal industry, John S. Fisher, Henry Hall, W.D. Kelley, and other formed the Clymer Brick and Fire Clay Company. Early in 1908, the new company began building a brick-making plant about a mile south-east of Clymer. By May 20, the Gazette reported : "The new brick plant is almost finished! This new Clymer industry will be turning out a product in a few weeks." The fire clay deposit was tapped at a high elevation on a hill behind the plant. The vein of coal above the vein of clay was mined first, and the coal taken directly into the factory's boiler plant. The, the clay was mined and dumped into a huge "dry pan," and ground up, or into a reserve supply pile. Various processes in the making of brick included mixing, grinding, and screening. Secondary handling, forming, pressing, and drying, and burning, resulted in an average production of 70,000 bricks a day. Three drying kilns, built in 1908, were located near the railroad yards. Electricity from a plant on the property made 24-hour-a-day production possible.

Late May, 1909 found the plant in high gear, with orders pouring in from three states. Superintendent C.W. Lenkard reported to shareholders that 500,000 buff paving blocks were en route to Staten Island, New York; 350,000 more to Baltimore, Maryland; and 330,000 more to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

Two years later, the Clymer Brick plant had "over one hundred men on the company payrolls," and several new kilns were under construction. The value of this plant to Clymer," stated a company spokesman, "is far more important than any of its other industries, including the mining operations, that are being carried on in our vicinity."

By the end of 1910, the plant at Clymer was established as the largest brick-works in the state. Production at the Clymer brick factory continued until the mid-nineteen-seventies. The last product made at the plant, nozzles used in the steelmaking process, reflected the same quality that had made the Clymer Brick Company well-known in the industry for seventy-five years.

In 1915, at the tenth anniversary celebration, John S. Fisher's letter, read aloud to the grandfathers and grandmothers of today's Clymer residents, concluded with a note that is appropriate today on the Day of the Diamond Jubilee: "So much for the past, now what for the future? It is true that Clymer presents an example of American enterprise. In scarcely any other country would it be possible to duplicate such an achievement. Much still remains."