Eileen Mountjoy

By the turn of the century, the company-owned mining town was firmly established as a way of life for thousands of western Pennsylvania coal miners. Many such communities grew up, seemingly overnight, in Jefferson, Clearfield, Cambria, and Armstrong counties.

On huge tracts of land once occupied by fields of growing grain or herds of grazing cattle, rows of identical houses now stood. Some of these new communities bore the names of prosperous New York businessmen or their wives: Walston, Adrian, Eleanora and Yatesboro.

The lifeline of the early coal towns was the gleaming track of a coal-carrying railroad, the Buffalo, Rochester and Pittsburgh Railway, which transported coal as far as the Great Lakes region. The extension of the BR&P from Jefferson County in 1902 opened up the rich, largely untapped coalfields of Indiana County. Beginning in 1903, the Rochester and Pittsburgh Coal and Iron Company build the town of Ernest along the extended line of the railroad. The new town was quickly populated, and Indiana County residents journeyed out on foot and in buggies to stare in amazement at the houses, tipple and partially constructed coke ovens standing on the formerly peaceful site of the old McKees' Mills.

Excitement over the founding of Ernest had barely died down, however, when the Indiana Democrat breathlessly announced the possibility of another new coal town in the vicinity of Indiana County. The Punxsutawney Spirit said in the January 25, 1905 article, "is authority for the statement that it is the intention of the Buffalo and Susquehanna Railway to extend its road south. The road, as presently located, runs almost parallel with the BR&P between Sykesville and Cloe. It is the intention (of the railroad company) to market the output of the Goodyears' coal field near Plumville."

In July, the same paper announced that the B&S had secured trackage rights over the BR&P from DuBois to Juneau and planned to build their own line form Juneau to Plumville. By March of the same year, construction on the B&S extension was underway. The B&S awarded a contract to a Potter County Firm, Greco and Company, which immediately formulated strategy for the construction of a seventeen-mile line between Juneau and Plumville.

In the next several months, a "shanty town" of hastily built cabins grew up on the Brown farm near Marchand. These "shanties" housed the nearly seven hundred laborers who arrived within the next few weeks as work on the railroad lines commenced with vigor. One month later, a corps of engineers, with transits and maps in hand, could be seen in Armstrong County near Wallopsburg (now Beyer) busily laying out streets and alleys for a new mining town. Some early residents claim the community was named in honor of a New York state Indian chief, while others believe, since the town was founded during the administration of Theodore Roosevelt, that it was named after the President's home, "Sagamore Hill."

Progress on the town was rapid. In August 1905 the Indiana Times reported that the B&S had awarded a contract to the Hyde-Murphy Company of Ridgeway, Pennsylvania, "to erect houses for the coal mines near Wallopsburg." Before construction began on the houses, however, William Hayes, aided financially by the B&S, built a sixty-room hotel, known as Hotel #19. At the hotel, on the site of the future town, the company doctor, officials and construction foremen lived in comfort while supervising the development of the new operation.

In the late fall of 1905 the railroad was completed to Sagamore, enabling the Hyde-Murphy firm to ship in materials for the construction of the first ninety houses. Double, or two-family houses, according to Hyde-Murphy's plans, had dimensions of twenty-eight feet by thirty feet and had five rooms on each side. Single houses measured twenty-four feet by twenty-six feet and contained seven rooms. In 1911, growth of the mines required still more workers, and the firm of Kline and Potts added thirty additional homes to the town. Later, the same company erected thirty small cabins in an area called "Shantytown," on the edge of town near the mule barn. Building continued at Sagamore as needed, and by the early 1920s, at least five hundred houses stood at the location.

The progress of Sagamore's mining plant kept pace with the building of railroad and town. The Goodyear family of DuBois, who according to a 1905 edition of the Indiana Evening Gazette were "the controlling factors in the Buffalo and Susquehanna Coal and Coke Company," purchases the Plumville field early in 1903, when the extensions of the railroad into Indiana County made out-of-state coal markets accessible. By August of 1905, the Indiana Times reported, "The Buffalo and Susquehanna Coal and Coke Company has made eight openings near Wallopsburg. They are located on land formerly owned by McKee Wilson, Harvey Roof, J.C. Anderson, M.C. Wyncoop, J.C. Delancy, Thomas McLee and Thomas McCausland. There are two openings on the McCausland farm."

At the end of 1905, the Department of Mines in Harrisburg included Sagamore in its annual report: "The Buffalo and Susquehanna Coal and coke Company has opened a big operation at a new town named Sagamore, on the extension of the B&S Railroad. In the fall, they had eight openings finished and were putting in more. It will be equipped with steel tipple, air compressors, electric generators, and everything that makes a modern mine. It will be one of the best in the state!" Within three years, the prediction made by the Department of Mines inspector proved to be a valid one. In 1905, four mines operated at Sagamore; officials first numbered the mines one through four, but later renumbered them eleven through fourteen. By 1908, four additional mines, fifteen through eighteen, were in operation. Numbers eleven and twelve were located in Indiana County and the other six in Armstrong County. A huge steel tipple stood midway between the drift openings. There, electric motors and chain hoists hauled loaded cars into the plant. Some of the largest air compressors made at that time provided air for coal cutting machines and drainage pumps inside the mines.

In 1913, Sagamore mines employed 806 men and produced an average of 600,000 tons of coal yearly. As is still true in mines today, many different occupations made up the work force at Sagamore. Mine foremen, assistant foremen, machine runners and loaders, trappers (doorboys), mule drivers, blacksmiths, carpenters, clerks and bookkeepers all labored together to keep the gigantic plant running smoothly.

The high quality of the coal mined at Sagamore formed the basis for the early success of the operation. The coal made an excellent fuel coal. Even at the close of 1908, when a general economic slump affected the national economy, the Indiana Evening Gazette reported: "The working of the B&S Coal and Coke Company at Sagamore have never been more successful than at the present time. The mines have all been working steadily for the past several months and all miners are given six days work every week. The tipple there, which is the largest in this part of the state, with a daily output of 1,000 tons, is being run to capacity almost every day."

The prosperity of the mines at Sagamore made the community a most desirable place to live. By 1908, most of the men who worked at the site made over $100 a month. The word spread, and soon the partially completed town bulged with new arrivals.

John ("Bounce") Kovalchick, who still makes his home in Sagamore, remembers the day in 1909 when he and his family moved there from Horatio in Jefferson County. John's father Nick "was a coal-cutter, and a good one." The family originally came from Czechoslovakia, and after several years in various Jefferson County mining town, decided to travel to Sagamore when they heard about the steady wages and good conditions at the mines of the B&S. John's first impressions of Sagamore are still vivid: "I looked down the valley; there were no trees. I saw hundreds of cows and it looked like the wild and wooly west."

He told his parents, "I'll be happy here; I hope I'll never leave!" These same cows later provided John with his first employment. Every coal town family who could possibly afford it kept a cow, and boys to young to work in the mines brought home a small income by taking the animals to pasture each morning and bringing them down again in the evening; a dollar a month was the usual rate of pay.

The town, as John recalls its appearance in 1909, "was twice as big as it is today." Houses in this popular town were at such a premium that every house - even the singles - sheltered two families, and some overworked housewives cared for as many as a dozen boarders.

A further influx of population occurred late in 1910, when the B&S Coal and Coke Company began the abandonment of its Onondaga mines near Punxsutawney. By November of that year B&S crews had removed all mine machinery and tools to Sagamore. Workers and their families soon followed. The Indiana Evening Gazette reported: "Practically all the miners formally employed at Onondaga have left and gone to Sagamore. The mines at Sagamore are working day and night and the miners who have been laid off at the various mines of the Company at other points find employment when they appear at the Company's offices there."

As the town expanded, other building were needed to supply the demands of the bustling community. In January of 1908 the B&S build a brick office building; H.A. Moulder, for who one of the avenues in Sagamore is named, became the resident superintendent. Moulder's home stood next to the doctor's office. At one time, three family doctors served the miners at Sagamore. Dr. Ralph K. Meader was one of the first; in later years Dr. James Coglin was well known for his untiring devotion to his patients. Several churches, Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Presbyterian, Greek Orthodox and Methodist, served the spiritual needs of the people. And, in the early days of Sagamore, immigrants from Sweden used one of the large single houses as a place of worship. Two schools, an elementary and high school, were built and used until the 1950's.

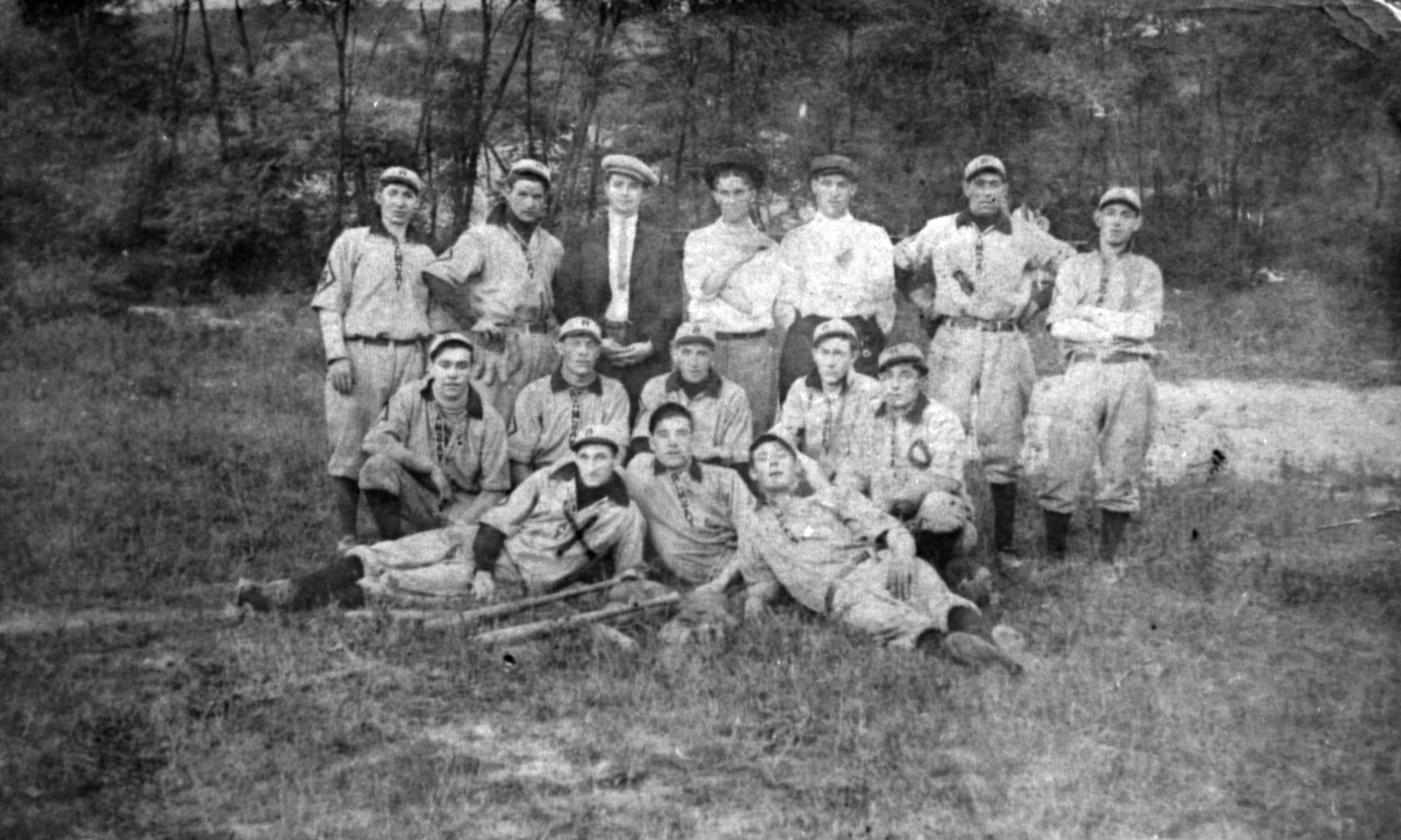

Early in the history of the town, baseball helped to fill the few leisure hours of the mining families. A fine ball field was at first laid out behind "Shanty Town," and later moved to a filled-in swamp behind the company store. A bandstand stood near the field so that Sagamore's own band, organized in 1909 by James Rutherford, could cheer on the home team. To the left of the hotel stood Hodgson's Community Center, a three-story, multi-purpose building which houses a theater, a restaurant and meeting rooms.

The Keystone Store, Sagamore's company-owned store, was built in 1905-1906. Throughout the late 1900s, A.R. McHenry served as storekeeper. By 1914, however, in spite of the company's unwritten rule that all miners must buy at the Keystone store, the town supported seven additional grocery and department stores. By the late twenties, the number of stores grew to eighteen, an included Lorenzo's, Mother Richard's Candy Store and Tallis and Evan's Clothing Store. The Kovalchick family built and operated a grocery sand meat store in 1909; the original store was destroyed by fire but was later rebuilt. In the western part of town a number of homes were privately owned and several other stores were operated, amongst them Johnson's Variety Store, George Turnbull's General Store and Joe Carroll's Ice Cream and Candy Store. Sagamore also boasted a wholesale brewery, owned and run by the Eisenhuth family.

Roy Orr, who today lives at Creekside RDl, went to work in the Sagamore company store as a boy in his late teens. The year was 1918, and the Sagamore mines were at peak production. As a general helper, Roy made deliveries with a horse and wagon, and helped wait on customers when the store was crowded.

The company store recalls Roy, "was like a whole group of stores under one roof." On the ground floor were groceries, with fresh fruits and vegetables brought in daily by train. At one of the grocery departments was a drugstore, where one could buy all kinds of patent medicines and sickroom needs. A dry goods department and cashier's office also occupied the first floor. Upstairs, on the second floor, a clerk sold simple, machine made furniture, beds and mattresses. In the basement, a butcher shop supplied fresh cuts of beef and smoked pork products.

Although there were other grocery stores in town, most residents preferred to buy at he Keystone store, where the quality of goods was high and items could be charged on the miners' "due bills." Roy remembers that in late afternoons, when school was over for the day and a work shift had ended, people lined up all along the counters, and several clerks were required to handle the customers.

He also recalls that due to the demand for labor at Sagamore, immigrants arrived every day. Sometimes, the newcomers' attempts at speaking English required translation by an older, more experienced clerk named Mr. Clemmons. Within a short time, however, new families were absorbed into the community, and, aided by friends and neighbors of the same nationality, soon felt at home in Sagamore.

Norman Coy, a retired miner who lives near Five Points, spent part of his boyhood in Sagamore. Norman's mother was also raised in a mining town: R&P's Adrian in Jefferson County. Norman came to Sagamore when his father was hired by the B&S to run a coal-cutting machine. Norman reminisces about the town with great enthusiasm: "They really lived it up in Sagamore," he recalls. "There was something going on all the time."

As a boy too young to go into the mines, Norman remembers the fun of growing up in the closely-knit community. In the summer, carnivals came to the town, and people traveled, mostly on foot, from Plumville, Beyer, Five Points and Elderton to ride on the Ferris wheel and buy ice cream at the confection stands. Often, the carnival brought along a professional boxer or wrestler who could talk the crowd into sending forth a challenger from the ranks of the locals. Arley Shaffer, Norman's uncle and a great favorite in Sagamore could usually be counted on to take up the gauntlet and thrill the onlookers with a few rounds in the ring. Tent revivals came to town, and if Sagamore children didn't participate, they at least enjoyed the excitement.

Childhood games of all kinds occupied small boys in Sagamore. "Shinney with a Can," was one favorite. Girls enjoyed playing hopscotch, tag, and making paper dolls from old Sears, Roebuck catalogs. Older boys looked forward to Halloween, when they operated under cover of darkness to upset outhouses "and anything else it was possible to turn over." The morning after this spooky holiday, a Sagamore resident who owned a buggy might find that, in addition to an upside-down outhouse, he also had to discover a way to retrieve his vehicle from the roof of his porch, or worse. From the top of the town's water tower.

In winter, ice-skating was popular on the pond created for the purpose of cooling the water used for the boilers at the power plant. The dam, which was located along the boney dump by the town cemetery, extended almost to the intersection of Routes 210 and 85 near Beyer. Then, in the evenings, "someone would roll up the rug and there'd be dance."

Lodge meetings, parades, band concerts, and wedding celebrations, which lasted all weekend filled the summer months. Pie socials and church activities abounded during the winter, when, in spite of frosty temperatures "people would think nothing of walking from Sagamore to the Grange near Five Points "for homemade pie and coffee."

Later, a few automobiles appeared in town: Norman remembers his father's 1916 Whippet, which was useful in the summer, but "come winter, you'd never try to drive it; you'd jack it up and put blocks under it "till spring." With true community spirit, Sagamore residents fortunate enough to own a car freely offered rides to all who were willing to brave the mud-filled roads.

Joe Jeffrey, who grew up in Sagamore but who now lives in Detroit, Michigan, also retains fond memories of his childhood in that particular mining town. Joe writes: "Have you ever stood in awe as you watched a powerful melodrama unfold at a medicine show? At least once a year a traveling medicine show would find a suitable spot somewhere in Sagamore, open up a small platform from the side of the wagon, and every night for a week provide wonderful entertainment. "Between acts men scattered throughout the crown and sold medicine that was guaranteed to cure all ills. One can never forget the thrill of watching Uncle Tom's Cabin,' and who can forget the unhappiness of the characters in the play Ten Nights in a Barroom?'"

Joe also remembers the bands of gypsies who came to Sagamore each summer and "camped in a grassy meadow near the creek. When they departed after a few weeks' visit, stories would circulate around the town about how a few gullible women were cheated when having their fortunes told, or someone would discover that the gypsies had helped themselves to many things without benefit of pay."

Foremost in Joe's memories of Sagamore, however, is what he calls "the human side of the story." He writes: "The people of Sagamore lived together almost as one family. Groups of people came from various parts of Europe and stayed together during the journey from eastern to western Pennsylvania as new mines opened up. "A great many of these groups settled in Sagamore, and that's what gave the town its character. "People helped one another, especially when someone in the family was sick or the breadwinner was injured."

While most memories of Sagamore are pleasant ones, the community, or course, had its share of tragedy and violence. "Accidents in the mines," says Norman Coy, "were a common occurrence." Although Sagamore throughout its history remained free of major explosions such as those in Ernest in 1910 and 1916, Norman remembers that "accidents were to be expected; you knew that so many men were going to be hurt."

In the early days, when miners' knowledge of English was often minimal, mishaps sometimes occurred due to a misunderstanding of mining procedures. During the period of heaviest immigration, incidents such as this one, reported in the Indiana Evening Gazette happened at Sagamore as well in other local mining towns: "A foreigner, whose name cannot be learned, was killed in the mines at Sagamore on Saturday. The man, who had been employed as a miner, was walking along the tracks in the mine carrying a long miner's auger. The auger in some way came in contact with the trolley wire and the poor fellow was electrocuted The dead man was middle aged; no near relatives reside in this country. Funeral services were held today and the body was interred in Plumville."

Not all the dead were "middle-aged." A State mine inspector's report on Sagamore for the year ending 1908 noted, among other deaths recorded that year, of "Frank Syrock, aged 17." Frank, the report stated, "was working in Sagamore mine #17, when he was "fatally injured by a fall of coal while helping his father to load coal in a room. Died three days later."

In the late 1920s, when the B&S began to replace some of the minemules with electric motors, a new type of injury followed this mechanization. "These motors," says Norman Coy, "had an unusually short latch or switch which often severely injured the men's legs when the switches came up through the floor." Accidents or fatalities in the mines seemed to emphasize the closeness of the community as neighbor helped neighbor. Often, however, in the days before compensation benefits for miners' families, widows were forced to take in washing to enable them to pay the rent on their company house.

Besides the deaths and injuries in the mines common to all coal towns, Sagamore also had its share of violence, as both memories and newspaper accounts indicate. The action at Sagamore, in fact, dates back to the days before the town was built. John Kovalchick, who owned the Sagamore Hotel for 21 years, states that on the building's opening date in 1903, a group of rowdy workmen "had a big fight and tore the whole front off!" The hotel throughout its existence remained the scene of frequent fistfights as well as an occasional shooting.

John, as the official innkeeper, recalls that, particularly on payday when the drinks flowed freely, "there seemed to be a fight going on in every corner."

Later, when some of the houses were completed and people moved in, a certain amount of friction was inevitable. John remembers that shortly after his family moved to Sagamore, when actual hand-to-hand combat threatened to erupt between two rival ethnic groups. "It looked like a small war," he says. "Both sides were equipped with pitchforks and axe handles." Happily, hotel personnel sent for state mounted cavalry troops who arrived in time to prevent fatalities.

Sometimes, firearms were in the wrong hands, as in this incident reported in a September, 1919 edition of the Marion Center Independent: Two Sagamore men, returning from a card game at a neighbor's were fired upon by unknown assailants who left two loads of buckshot in the legs and back of one man and three revolver bullets in the legs of the other. Later that month, the Independent noted that a stealthy crew of robbers collected a total of $375 from various homes, then "stole a Reo car from a garage and fled." Later, in the early twenties, a new and even more sinister band of thieves organized in Sagamore. These cunning criminals, John Kovalchick relates, "gained entrance to his victims' houses after using a hose to pipe gas in through keyholes and open windows, leaving them too groggy to resist.

Sagamore residents fought back against crime in their community, and from the earliest days, company-hired lawmen patrolled the town. The most memorable of these brave individuals is the intrepid Cal McKee, a large man of grim determination who is still remembered with respect by many residents of Indiana and Armstrong counties. Despite the accidents, robberies and sporadic shootings which were common to all coal towns of the period, Sagamore is basically remembered by former residents as a particularly fun-loving and prosperous community.

The mines reached maximum production during World War One, and the boom continued unto the early 1920's. By that date, John Kovalchick estimates that 1,600 men worked at Sagamore and the total population of the town reached 3,000. Then, in mid-1924, a major shutdown of the mines occurred. This resulted, in part, from coal operators' inability to maintain the terms of the Jacksonville Agreement as demanded by the UMWA.

The coalmines in most of western Pennsylvania remained virtually closed for two years and the quality of life in Sagamore as well as in other nearby coal towns suffered a dramatic change. John will never forget the day the company ordered the men out of the mines. "Within weeks," he says, "the union lost out completely and many men took their families to the cities." Union men who remained received notices of eviction from company houses. Later, officials took stronger measures against more persistent activists; company police arrived and removed both furniture and people from their homes. Many small storeowners soon declared bankruptcy as old customers disappeared, often leaving unpaid bills behind. Non-union miners, called "scabs" by residents of Sagamore, were brought in by the Coal Company to occupy the evicted houses.

Union men at Sagamore, among the last in District 2 to surrender their charter, retaliated by dynamiting company houses and singing spirited union songs as they paraded in front of the hotel. Within a year, however, despite these last-ditch efforts, most of the original settlers of Sagamore were gone. For almost a decade, the mines at Sagamore remained non-union; the population changed constantly as families constantly in and out. The mines went on "short-time," and the amount of money in pay envelopes dwindled.

Roy Blystone, also of RD 1 Creekside, remembers what it was like to work at Sagamore then. Roy went into the mines at Sagamore in 1927, when he was 15 years old. Like all beginners, Roy was assigned an experienced "buddy," in this case his brother-in-law, Harry Sink. The two were put to work in mine #13, near the old St. John's Lutheran Church. (Now the Sagamore Gospel Center.) As the face of the mine was three miles in, Roy and Harry preferred to use the short cut "down the airshaft." (Near what is now Star's Service Station in Plumville.) In the shaft, 24 flights of steps, eight steps to each flight, twisted to the bottom. "It didn't take long to walk down," Roy recalls, but coming back up again in the evening was an awful drag." Once inside the mine, "you had to nail your lunch bucket to a post or the rat's would get it, They'd claw the lid right off your dinner pail." But the presence of the rats was a good sign: "Where the rats were, you knew you were safe."

Roy's job in the mine consisted of shooting down and hand-loading the coal previously cut by men with punching machines. "One cut," says Roy, "made a day's work. We made three or four dollars a day." Roy and his buddy loaded an average of 12 two-ton cars a day in an eight-hour shift; mules hauled the coal cars to the heading where motors pulled them to the surface.

While the B&S had good foremen and maintained their mines in a safe condition, Roy remembers at least one incident of the type that took place in the days before workers' rights were protected: A man named Carl was working alone one day while his buddy was home sick. Carl labored on by himself, in a room which was, on that particular occasion, knee-deep in muddy water. "You either worked in the water, or you went home without your pay," Roy recalls. As the morning wore on, one of the foremen came by to see how the work was progressing, and commented on the absence of Carl's buddy. "Oh, him!" Carl replied, "he's gone down under after a shovelful. He's be up for air after while!" Far from finding this remark humorous, "the boss laid Carl off three days for being smart."

The new UMWA organized in Sagamore in l933, Roy remembers. "Organizers came to all the towns, and several hundred of us met in a big field near present-day Keystone Lake. That field looked like a bandstand," he says. We sure felt good!" Though the coming of the union improved conditions for Sagamore miners, the town never fully recovered from the 1924 shutdown. The population further declined in the 1930's, when the great depression affected the coal industry. Many houses were vacant and were torn down, often for firewood.

A brief revitalization occurred at Sagamore in 1943, when, because of the demand for coal brought about by WWII, R&P Coal Company leased Sagamore mines #13 and #16 from the B&S. The mines were permanently closed and abandoned in 1950. In the early l950.'s the Kovalchick Salvage Company bought the mining plant, and in the l950's the tipple was demolished. The mighty powerhouse, known at one time as "the largest one in the world," was also torn down and the bricks sold. The company store burned down a few years later.

One landmark, however, fittingly remains. The Sagamore Hotel, after 73 years of continuous service, still stands, in good repair and wearing a fresh coat of paint. Today, the old building looks much as it did when the Memorial Day parade passed by on its way to the cemetery. At the hotel, a passerby can still find a good cup of coffee and good conversation, and imagine the days when, in the words of Norman Coy, "There was no place like Sagamore!"